Issue 25

ProfessorYoshiharu Tsukamoto

Department of Architecture and Building Engineering, School of Environment and Society

Integrating existing design theories with the concept of behaviorology

When air in a room warms up, it rises. Cold air outside your window causes condensation on the glass. Such phenomena, caused by components obeying physical principles — sunlight, heat, wind, and humidity — are referred to as natural behavior.

As people mature and acquire experiences in society, they adopt a certain behavior —human behavior. This behavior, or culture, develops under specific influences affecting a particular region — influences such as weather, climate, and religion.

So what is architectural behavior? Professor Yoshiharu Tsukamoto defines it as an architectural design theory closely connected to the behavior of nature and people. While behavior generally suggests the presence of motion, architectural behavior does not. For example, in areas where strong sunlight creates intense heat, buildings will often be equipped with small windows to reduce the effects of this heat. These buildings lining the streets create unique cityscapes. Buildings also transform over time according to changes in society. These are architectural behaviors.

"Producing sophisticated architectural design requires that we integrate various considerations on a wide range of factors. In spite of this, the focus of conventional architectural design theories is often quite scattered, making it impossible to perceive the building in a comprehensive manner. However, if we summarize these different components with a single term — architectural behavior — we can integrate them and begin to see the bigger picture. This is why I developed a comprehensive theory that considers design from the perspective of architectural behavior."

Architectural design cannot be realized through architectural sense alone. Tsukamoto emphasizes that logic is also essential for gaining the empathy of the numerous people engaged in the design phase.

"In order to build something, we need to consider design that benefits society, something that satisfies people. Doing so requires not only the design of a beautiful structure, but also logic. Logic allows us to share with society what we have now, and where we are going in terms of architecture."

This logic is provided by architectural behavior.

Implementing the concept into the Institute's facilities

As an example that incorporates architectural behavior, Tsukamoto cites the Tokyo Tech Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) building, for which the professor provided the initial design. An international base for research in the field of bioplanetology, the building was completed in October 2015 in the Ishikawadai Area of Ookayama Campus. It has an exposed concrete finish, but also features sliding Japanese paper doors. Although the design evokes a Japanese feel, Tsukamoto emphasizes that it was based on the concept of architectural behaviorology, derived from natural and human behavior.

"Air pockets created between the sliding doors and windows function as a thermal buffer zone.1 Opening and closing the sliding doors allows occupants to control radiant heat transfer from the windows as well as ventilation. Also, this opening and closing adds an element of life to the building. Viewed from the outside, the light glowing from these sliding doors is gentle, like the light from a paper lantern, and is in harmony with the surrounding residential area."

Windows have been a theme of behavioral study for roughly ten years. They bring together natural, human, and architectural behavior.

"Through windows, natural components such as light, heat, wind, and humidity interact and reveal different behavior at different times. Meanwhile, human behavior around windows is unique, reflecting weather, climate, and religion. When we look at buildings along a street, we sometimes see that they all share the same window structure. This commonality of window design integrates the variations of the buildings to create beautiful scenery. This is what architectural behavior is about."

Tsukamoto and his research group have published three books, WindowScape: Window Behaviorology, WindowScape 2: Window and the genealogy of streetscape, and WindowScape 3: Windows and workspace, all of which summarize field surveys on window behavior, both at home and abroad. His research group is also engaged in architectural design. The ELSI building is just one of their projects.

"I think buildings on a campus should function to improve the spaces surrounding them. I tried to design a basic structure for the university campus that is different from libraries and halls resembling monuments. Overseas researchers often spend years at this facility, so I designed Japanese-style rooms in an attempt to provide a unique sense of local hospitality. I also designed a spatial structure in which the use of wood increases as we move from the concrete frame towards the interior finishing and windows, the parts that people interact with most often."

1. ELSI Building — Steel reinforced concrete structure with three floors above ground and basement floor

2. First-floor hall — Ideal for seminars, workshops, and public lectures

3. Sliced ore at entrance from lab located at site before ELSI construction

4. ELSI AGORA — 2nd-floor gathering space with paper sliding doors on windows

Installing 4,570 solar panels

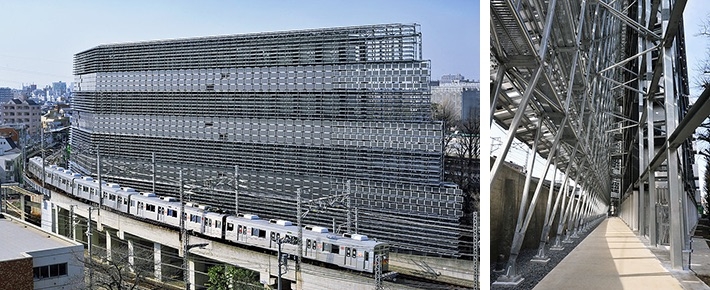

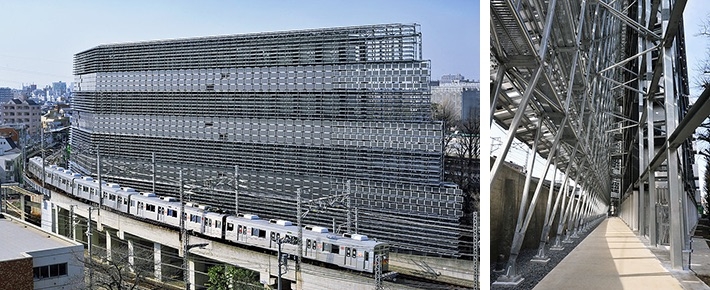

Tsukamoto's research group was also involved in the design of the Environmental Energy Innovation (EEI) Building, completed in the Ookayama North Area in February 2012. As the name implies, the facility is a center for research on environmental energy technology. It utilizes a wide variety of systems designed to create and save energy, with the goal of reducing CO2 emissions by more than 60 percent compared to average laboratory facilities on campus.

"The greatest building design feature of EEI is that the solar envelope,2 fitted with 4,570 solar panels, is designed as a structure separate from the actual building. This enables the solar panels to extend to the property boundary, and allows tilting of the panels to maximize efficiency. All panels are accessible from service catwalks to allow for future replacement. A buffer zone is created between the building and the solar envelope. Warm air in the buffer zone flows upward towards the top of the building, helping to keep the panels cool. This prevents heat from building up behind the panels, reducing the deterioration of power generation efficiency."

EEI Building — Neighborhood landmark with detached solar panel envelope

"EEI Building" filmed and edited by Diego Grass P. Copyright © 2017 OnArchitecture

Architecture belongs to social reality. New topics of research are found not in the laboratory, but in communities. Researchers sometimes discover them in dark, unexpected places such as disaster sites.

One month after the Great East Japan Earthquake, a groups of architects established ArchiAid, a disaster relief and restoration support network of which Tsukamoto is a founding member. Thinking that involvement in actual restoration work would be a great educational opportunity, the professor asked students in his research group to join recovery projects on the Oshika Peninsula of Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture. They also participated in the restoration of a shrine located in Ooyagawahama, one of 28 beaches on the peninsula, which had served as a symbol of hope for the people in the local community.

Learning from pre-industrial revolution trial and error

What the group learned from the restoration support activities was a new architectural designing methodology, prompting Tsukamoto to apply ethnography3 approaches to his work.

"When, for example, a client in Tokyo asks us to design a building, the property, budget, construction period, and program are usually determined along with a myriad of other conditions subject to laws and regulations regarding architecture and urban planning. When disaster strikes, however, the original plans are often lost, and we need to start from the basics after listening to the people in the community, much like with field surveys in ethnography research. This also applies to our study on architectural behavior of windows, during which we conducted many field surveys throughout the world. I remember feeling that real architectural thought could begin from such surveys. Since then, I have come to think that the ethnography approach to architectural design is truly useful."

These approaches have also led to an attempt to examine architectural behavior from the viewpoint of ethnography. The aim is to study architecture rooted in regional climate and lifestyle, and then apply the lessons learned to today's architecture. One subject of study is the traditional townhouse, or machiya, in Kyoto. Kyoto is hot in the summer, and cold in the winter. It also has a humid climate. Such conditions influenced the development of a unique housing design that features a living section called ie and a storefront called mise, both together on a long, deep plot of land with narrow frontage.

The wisdom applied to the architectural structure of such townhouses is evident in the comfortable living conditions created in the environment available. The lattice wall on the street side allows wind to pass through the structure while shading the interior and providing privacy. A courtyard in the middle of the townhouse lets in sunlight and allows warm air from inside the building to vent out, providing comfort in the summer season.

"Environmental control utilizing the lattice and courtyard is both interesting and agreeable when compared with industrialized methods such as the air conditioner. In order to avoid design based on facilities and equipment provided by industry, it is important for us to learn from the wisdom developed through trial and error by those who lived before the industrial revolution. Computers do not have such a history. However, architecture is full of such development. I believe it is beneficial for us to apply such wisdom to contemporary architecture."

Naturally, both undergraduate and graduate-level students in Tsukamoto's research group are eager to pursue architectural design. While being deeply involved in research that often spills over into design, they gradually develop a crucial sense of logic. Tsukamoto gives all his students the freedom to explore their own research topics within the broad theme of architectural behavior.

"I encourage each student to write a thesis that best represents him- or herself. Why? Because thinking for ourselves when designing a building is of the utmost importance."

The principles of behavior guiding Tsukamoto the architect undoubtedly illuminate his path as an educator.

Graduate-level seminars — Multicultural discussions over tea

1 Buffer zone

A space or structure provided to reduce impact of noise, vibration, or heat

2 Envelope

Exterior structures that wrap a building

3 Ethnography

Historical changes of tangible and intangible phenomena that have been passed down from one generation to the next

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

Profile

- 2016 - presentProfessor, Department of Architecture and Building Engineering, School of Environment and Society, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 2015 - 2016Professor, Department of Architecture and Building Engineering, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 2000 - 2015Associate Professor, Department of Architecture and Building Engineering, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1994Doctor of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Building Engineering, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1992Co-established Atelier Bow-Wow with Momoyo Kaijima

- 1987 - 1988Visiting Student, Ecole Nationale Supérieure d'Architecture de Paris-Belleville (ENSAPB)

- 1987Bachelor of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Building Engineering, School of Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

Tsukamoto has also been visiting professor at Harvard University, University of California, Los Angeles, Cornell University, Rice University, Columbia University, Delft University of Technology, and the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

The Special Topics component of the Tokyo Tech Website shines a spotlight on recent developments in research and education, achievements of its community members, and special events and news from the Institute.

Past features can be viewed in the Special Topics Gallery.

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.