Tokyo Tech News

Tokyo Tech News

Published: August 31, 2012

One of the biggest natural disasters ever to hit Japan occurred on 11th March 2011. The magnitude 9.0 earthquake and the subsequent tsunami caused widespread devastation across the east of the country. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant on the east coast north of Tokyo lost its ability to cool its reactors as a result of damage by the earthquake and tsunami. This led to vast numbers of radionuclides (radioactive isotopes) being released into the atmosphere.

It is only now that scientists are beginning to piece together and understand the scale of the radioactive contamination on the land and in the seas around Japan. Much data is still required, and the decontamination projects will continue for many years to come.

Naohiro Yoshida of the Department of Environmental Chemistry and Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology, together with Jota Kanda of Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, recently published a ‘perspectives’ article in the high profile journal Science1. The article highlights the key findings so far about the scale of radiation released from Fukushima, and outlines how radionuclides released and transported in the atmosphere, and deposited on land and in the oceans.

“As a stable isotope geochemist, a fundamental part of my job is tracing material cycles through stable isotopes,” explains Yoshida. “I work with inter-disciplinary research groups responsible for mapping and monitoring the movements of radioisotopes, and in this particularly serious case, radionuclides from the nuclear disaster.”

Yoshida's article highlights some of the key findings from research undertaken since the disaster last year. Around Fukushima itself, contamination is such that it is still preventing thousands of local people from returning to their homes.

Cesium isotope 137 (137Cs) and Iodine isotope 131 (131I) were the two main fission products released in huge quantities into the atmosphere. In the first month after the tsunami, 150 million billion becquerels (Bq) of 131I and potentially up to 50 million billion Bqs of 137Cs were released into the air around Fukushima.

The radionuclides migrated not only through the atmosphere but also on the surface soils and seas. Due to prevailing westerly winds in the early spring of 2011, many of the radionuclides spread out over the North Pacific Ocean. Researchers now know relatively well where the 137Cs was deposited on the land surface, but the future consequences are yet to be fully assessed. For example, it is estimated that around 30% of the emissions from Fukushima were deposited on land.

“On land, the terrestrial ecosystems suffer greatly,” explains Yoshida. “The air-terrestrial-water-land surface interactions are all affected, and the radiation can stay for many years. Cesium in particular clings to clay minerals, and thereby stays predominantly in the top soils.”

Once the radionuclides are incorporated in material cycles, they continue to migrate, flowing down rivers, collecting in lakes and the ecosystems. This in turn can lead to localized collecting of radiation in hot spots around river estuaries, for example. The true extent of this issue in Japan is unknown, and may only present itself in years to come.

131I is far harder to trace. Its half life is only 8 days, meaning that only one tenth remains every 3 weeks or so after a nuclear disaster. However, the long term effects of exposure are dangerous, leading to cancers and tumors. Another iodine isotope, 129I, is a useful trace for 131I, as Yoshida explains:

“129I lingers in the atmosphere far longer, meaning that monitoring it and creating detailed models of the distribution may lead to reconstruction of 131I in the early days. An investigation into 129I levels in Japan is crucial.”

The radiation present in the oceans is also cause for concern. Although the initial peak in radiation fell away quickly as the particles were washed away in the ocean, contamination in fish off the east coast of Japan is in places still too high to allow commercial fishing to recommence. A rapid and wide-ranging survey of the marine food web is needed, along with studies investigating radionuclides present in the seafloor.

Other radionuclides, such as plutonium, also need to be tracked in order to establish long term health effects for the local population.

Yoshida and Kanda call for widespread scientific investigations and research into all radionuclides and their dispersion following the Fukushima disaster. Highest priority must of course be given to the decontamination of residential and highly populated areas. However, in order for this work to be effective in the long run, full knowledge of the different radionuclides, their whereabouts and their strength is paramount.

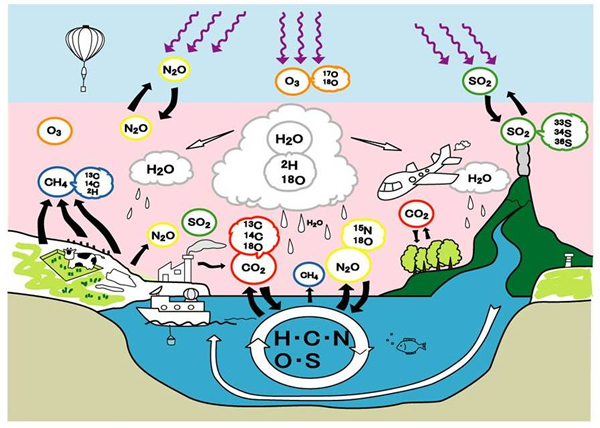

Tracing material cycles through isotopomers

Reference

Naohiro Yoshida

Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Environmental Chemistry and Engineering

Professor