Scientists at the Earth-Life Science Institute at the Tokyo Institute of Technology report in Nature (22 February 2017) unexpected discoveries about the Earth's core. The findings include insights into the source of energy driving the Earth's magnetic field, factors governing the cooling of the core and its chemical composition, and conditions that existed during the formation of the Earth.

The Earth's core consists mostly of a huge ball of liquid metal lying at 3,000 km beneath its surface, surrounded by a mantle of hot rock. Notably, at such great depths, both the core and mantle are subject to extremely high pressures and temperatures. Furthermore, research indicates that the slow creeping flow of hot buoyant rocks—moving several centimeters per year—carries heat away from the core to the surface, resulting in a very gradual cooling of the core over geological time. However, the degree to which the Earth's core has cooled since its formation is an area of intense debate amongst Earth scientists.

In 2013 Kei Hirose, now Director of the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) at the Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech), reported that the Earth's core may have cooled by as much as 1,000 ℃ since its formation 4.5 billion years ago. This large amount of cooling would be necessary to sustain the geomagnetic field, unless there was another as yet undiscovered source of energy. These results were a major surprise to the deep Earth community, and created what Peter Olson of Johns Hopkins University referred to as, "the New Core Heat Paradox", in an article published in Science.

Core cooling and energy sources for the geomagnetic field were not the only difficult issues faced by the team. Another unresolved matter was uncertainty about the chemical composition of the core. "The core is mostly iron and some nickel, but also contains about 10% of light alloys such as silicon, oxygen, sulfur, carbon, hydrogen, and other compounds," Hirose, lead author of the new study to be published in the journal Nature. "We think that many alloys are simultaneously present, but we don't know the proportion of each candidate element."

Now, in this latest research carried out in Hirose's lab at ELSI, the scientists used precision cut diamonds to squeeze tiny dust-sized samples to the same pressures that exist at the Earth's core (Figure 1). The high temperatures at the interior of the Earth were created by heating samples with a laser beam. By performing experiments with a range of probable alloy compositions under a variety of conditions, Hirose's and colleagues are trying to identify the unique behavior of different alloy combinations that match the distinct environment that exists at the Earth's core.

Figure 1. Diamonds to squeeze a sample to ultrahigh pressures corresponding to those of the Earth's core (greater than 135 gigapascals). The samples are heated under pressure to high temperatures of the core (about 4,000 kelvins and higher) by being irradiated by a laser through diamonds.

The search of alloys began to yield useful results when Hirose and his collaborators began mixing more than one alloy. "In the past, most research on iron alloys in the core has focused only on the iron and a single alloy," says Hirose. "But in these experiments we decided to combine two different alloys containing silicon and oxygen, which we strongly believe exist in the core."

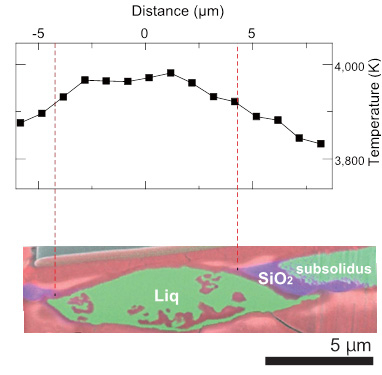

The researchers were surprised to find that when they examined the samples in an electron microscope, the small amounts of silicon and oxygen in the starting sample had combined together to form silicon dioxide crystals (Figure 2)—the same composition as the mineral quartz found at the surface of the Earth.

Figure 2. Experimental result on crystallization of liquid Fe-Si-O at 133 gigapascals and about 4,000 kelvins, corresponding to the condition at the uppermost core. The X-ray elemental map shows the SiO2 crystals (purple) were formed from liquid (green) at low temperature part.

"This result proved important for understanding the energetics and evolution of the core," says John Hernlund of ELSI, a co-author of the study. "We were excited because our calculations showed that crystallization of silicon dioxide crystals from the core could provide an immense new energy source for powering the Earth's magnetic field." The additional boost it provides is plenty enough to solve Olson's paradox.

The team has also explored the implications of these results for the formation of the Earth and conditions in the early Solar System. Crystallization changes the composition of the core by removing dissolved silicon and oxygen gradually over time. Eventually the process of crystallization will stop when then core runs out of its ancient inventory of either silicon or oxygen.

"Even if you have silicon present, you can't make silicon dioxide crystals without also having some oxygen available" says ELSI scientist George Helffrich, who modeled the crystallization process for this study. "But this gives us clues about the original concentration of oxygen and silicon in the core, because only some silicon:oxygen ratios are compatible with this model."

Reference

Authors: |

Kei Hirose1, Guillaume Morard2, Ryosuke Sinmyo1, Koichio Umemoto1, John Hernlund1, George Helffrich1 & Stéphane Labrosse3 |

Title of original paper: |

Crystallization of silicon dioxide and compositional evolution of the Earth's core. |

Journal: |

Nature |

DOI : |

|

Affiliations : |

1Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan.

2Institut de Minéralogie, de Physique des Matériaux et de Cosmochimie, UMR CNRS 7590, Sorbonne Universités—Université Pierre et Marie Curie, CNRS, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, IRD, 4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France.

3Université de Lyon, École normale supérieure de Lyon, Université Lyon-1, CNRS, UMR 5276 LGL-TPE, F-69364 Lyon, France. |

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.