Thirty-nine professors engaged in teaching, research, and administration over the years at Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) will retire at the end of the 2013 academic year in March 2014. We were honored to interview two of them before they leave the Institute. They shared with us their memorable episodes and prospects for the future.

Tell us about your field of specialty.

My specialty is biology. While molecular biology is mainstream in the Graduate School of Bioscience and Biotechnology at Tokyo Tech, I deal with more conventional biology, namely biology at a macro level focusing on individual organisms, tissues, and ecological systems. In other words, I study a rather "unpopular area within the field of biology." Within this marginal area of individual-level biological studies, animals with brains, such as monkeys, are the most popular subjects of study. However, I tried to study organisms without brains as much as possible, because I believe the study of animals or organisms with brains is not enough to understand everything about the world of living things. The focus of my research, therefore, was organisms that people don't usually talk about, including echinoderms, such as sea cucumbers and sea urchins, as well as sea squirts and seashells.

Holothuria arenicola, one of the sea cucumbers of study

I arrived at the understanding that an organism, as a result of evolution, comes to occupy a specific place in the world by its mere existence. When we investigate the significance of the mechanism that allows the skin of sea cucumbers to sometimes harden and other times soften, we find that the way in which a sea cucumber "exists" in the environment is completely different from the way in which other organisms "exist." That's why we can say that sea cucumbers create their own unique world. A sea cucumber has neither a brain nor sensory organs. A sea cucumber's world can only be understood from the perspective of sea cucumbers. In the same way, mice have their own world and elephants theirs. The way a species "exists" is totally different from one species to another. If we look at mankind this way, we may be able to see the world from a completely new perspective. I pursued such studies for thirty years.

What made you choose biology as your field of study?

I was born right after World War II ended; I am a baby boomer. When I was a child, there were still many ruins from the fires. The economy grew dramatically after that. Tokyo hosted the Olympic Games when I was a 1st-year student in high school. I took my university entrance exams in the middle of the high economic growth period. It was a period in which manufacturing was flourishing, and students flocked to engineering departments in universities and colleges, not least to Tokyo Tech. Most of the students who were good at mathematics applied to engineering departments. Meanwhile, I was sort of an outlier, and genuinely wanted to pursue a basic course of study rather than being useful to society.

This preference of mine limited my options to studying either in the faculty of science or in that of literature. In those days, elementary particles were the star in the field of science. On the other hand, the study of literature seemed to probe nothing but human minds. Neither one of them alone seemed enough, by any stretch of the imagination, to understand the world that surrounds us. Then I thought that I might want to take a look at the world from a viewpoint halfway between elementary particles and human minds. Ultimately, it was the field of biology that satisfied this condition.

I understand that you taught at the University of the Ryukyus before you joined Tokyo Tech.

On location at Sesoko Station, University of the Ryukyus

Yes, I was at the University of the Ryukyus from 1978 through 1991. Okinawa, as it may be expected, offers a breeding ground completely different from that of Honshu for the development of culture. Naturally, the people have a unique way of looking at things. Of course, the biota is also distinct. Even time passes at a different pace. It is this environment that made me realize the importance of understanding different cultures and different worlds, and think that sea cucumbers, elephants, mice and all other creatures have their own unique worlds completely different from ours. In fact, Okinawa shaped my view of the world into what it is now.

What is your impression of Tokyo Tech?

I am very grateful to Tokyo Tech for giving me an opportunity to teach and conduct research for twenty-two years. Our liberal arts curriculum is widely known for having a galaxy of brilliant faculty members. Being able to teach biology in such a wonderful environment was more than I could have hoped for. I was very lucky to be offered the position. I am truly grateful from the bottom of my heart for the opportunity I was given to teach and conduct research at Tokyo Tech.

Finally, would you mind sharing your future plans with us?

Japan's elderly population is growing rapidly. Biologically, living things are not supposed to survive long after their reproductive periods are over [laughter]. I convinced myself as a biologist that nurturing our next generation is a reproductive activity in the wider sense, and that, if I continue to be involved in education, I am still "active." Therefore I can justify living. Fortunately, an elementary school Japanese language textbook printed a piece of mine and these days I visit schools in various regions to give lectures. Children seem to enjoy them very much. I would like to continue such activities with the motto, "after retirement, one shall work to nurture the next generation."

I hear that you specialized in humanities when you were a student.

When I entered the University of Tokyo, I was interested in molecular biology and majored in Natural Sciences II in the College of Arts and Sciences. Soon after my enrollment however, strife broke out between students and the university, the "University of Tokyo Strife." There were no classes during my 2nd-year, and all students did was discuss how Japanese systems and universities should be managed. Despite my initial intention to study molecular biology, the more involved I became in those discussions, the more my interest was drawn to the subject of humans and societies. So, after I finished the required liberal arts curriculum, I switched my major to sociology and studied in the Department of Sociology.

Could you share with us some of your stories from the Department of Social Sciences?

If truth be told, I experienced a lot of culture shock. Compared to science-related studies, sociology demanded an overwhelming amount of knowledge. I almost thought that my classmates had entire dictionaries embedded in their heads. Somehow I managed to catch up with them by the time I completed my master's program. It was during my studies in the Department of Sociology that I encountered the theory of social systems, which became the focus of my studies as a theorist.

In addition, my supervisor constantly repeated like a Buddhist mantra that "scholars must attain both theories and empirical research." In this context, in order to attain empirical research, I was put in charge of the third nationwide survey on social classes, namely the "National Survey on Social Stratification and Social Mobility," which the Japan Sociological Society has conducted every ten years since 1955. I became a research assistant to the supervisor halfway through my studies in the doctoral program, and put my heart and soul into conducting the survey and organizing workshops for three and a half years until I transferred to Tokyo Tech. The experience of handling these challenging projects provided me with a solid foundation as a researcher.

After that you joined Tokyo Tech as an associate professor?

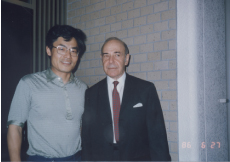

Pleasant talk with Leonard Bloom at my house

Yes. It was 1979. I was about to turn thirty years old. First I taught courses in the liberal arts curriculum for about seven years. It was a period in which I could focus on my life's work, which is research in the theory of social systems. In 1986, I completed my dissertation, and in the same year, my overseas research proposal was accepted by the then Ministry of Education. This gave me a year-long opportunity to study at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, home to studies on social stratification. I returned to Japan in September 1987 and was promoted to professor the following year. From then on, things became really rough.

Enormous Contribution to the Establishment of the Graduate School of Decision Science and Technology.

I have been engaged in education and research together with professors of sociology, social systems, and science and technology in the Graduate School of Decision Science and Technology since the establishment of this multidisciplinary graduate school in1996. Prior to this, we underwent a lot of hardships. The year after I was promoted to professor in 1988 was when I earnestly began advocating for the establishment of such a graduate school. There were two previous unsuccessful attempts to establish a graduate school that integrated humanities and science. Both times I followed procedures and submitted proposals to the then Ministry of Education with rough budgetary estimates, but the Institute was not ready to open such a graduate school.

I made up my mind to try a third and final time to push for the establishment of such a graduate school. Finally, the Graduate School of Decision Science and Technology was established with the purpose of opening a new research domain integrating humanities and science in four departments: the Department of Human System Science, the Department of Value and Decision Science, the Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, and the Department of Social Engineering. The establishment of the Graduate School of Decision Science and Technology took eight years from my first proposal to realization. This significant change is an example of my theory of "Self-Organization."1

What kinds of future activities would you like to be involved in?

I have so much work to do, including recent committee work on problems related to high-level radioactive waste from nuclear power plants and its risk to society, that I am buried up to my neck in work. However, the area I'm putting the most effort into right now is the "potential of civilization science." The Renaissance, which started in the 14th century, changed our view of mankind. Then the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century secularized society. Subsequently, the 17th century witnessed a scientific revolution, and the 18th century saw democratic revolutions. After that, the Industrial Revolution took the world by storm from the latter half of the 18th century to the 19th century. Through these changes, the foundations of modern society were at long last completed. More than four centuries have passed since the Renaissance.

The National Diet of Japan, Energy Investigating Committee (26th preparatory meeting)

Actually, I think similar changes started in the 1980s. While the transition to a modern society took four centuries, I have the feeling that this time around the transformation may take only about a century. A new civilization will begin possibly in the 22nd century. And, it is information technology that will facilitate the transformation of civilization into a new form, which is inevitable at this point. Thinking about it, I am so excited that I can hardly sit still.

To change oneself at one's own initiative, regardless of changes in the environment, rather than changing to adapt oneself to the environmental changes. Thus it is equivalent to the metamorphosis of a pupa so to speak, since it is self-reformation by the power of implosion and not adaptation to the environment.

Profile

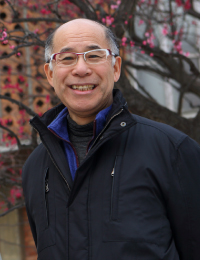

Tatsuo Motokawa

- 1991Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1991Assistant Professor at University of the Ryukyus

- 1986 - 1988Visiting Associate Professor, Duke University

- 1978Lecturer, University of the Ryukyus

- 1975Assistant Professor, University of Tokyo

- 1971Doctor of Science, Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo

- 1971Bachelor of Science, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Tokyo

- 1948Born in Sendai, Miyagi prefecture

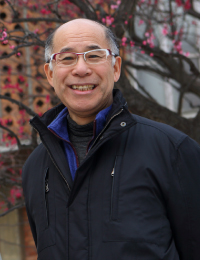

Takatoshi Imada

- 1996Professor, Department of Value and Decision Science, Graduate School of Decision Science and Technology, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1988Professor, School of Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1986Honorary Fellow, University of Wisconsin-Madison

- 1986Doctor of Philosophy, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1979Associate Professor, School of Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1975Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Faculty of Letters, University of Tokyo

- 1975Graduate work at the Department of Sociology, Graduate School of Sociology, University of Tokyo

- 1975Master of Sociology, Graduate School of Sociology, University of Tokyo

- 1972Bachelor of Arts, Department of Sociology, Faculty of Letters, University of Tokyo

- 1948Born in Kobe, Hyogo prefecture

The Special Topics component of the Tokyo Tech Website shines a spotlight on recent developments in research and education, achievements of its community members, and special events and news from the Institute.

Past features can be viewed in the Special Topics Gallery.

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.