Thirty professors engaged in teaching, research and administration over the years are retiring at the end of the 2014 academic year in March 2015. We were lucky to catch up with two of them before they leave the Institute. They shared their memories and plans for the future.

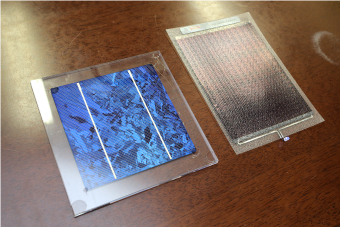

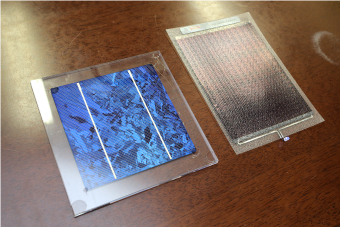

Please tell us about the development of solar cells as one of the vital alternative energies that will replace petroleum.

My research on solar cells began on 1972, when I was in the first year of my master's program. At the time, I was studying transistors in semiconductors; but Professor Kiyoshi Takahashi, who was my academic supervisor, told me that the age of the solar cells was coming and that I should catch the wave. He had great foresight, and the idea captivated my imagination, so I took his advice. That's how I got started.

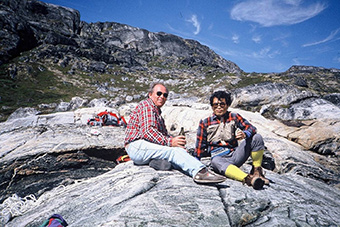

In October 1990, Konagai stayed in Algeria for JICA's university

support project at the University of Science and Technology of Oran.

He spent weekends studying the natural environment in the desert.

Two years later in 1974, a long term research and development project for new energy technologies called the Sunshine Project was initiated in Japan. This project sparked even more interest in the field. Then a few years later, in 1980, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry launched the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO), which was a forerunner of the now common industry-university cooperation. It isn't an exaggeration to say that all of my achievements were made possible because I had the chance to be involved in this exciting area from the beginning.

How far do you feel the development of solar cells has come in the overall picture?

I expect solar cells to become the core energy of the nation around 2040 to 2050, which means we still have 30 or 40 years ahead of us. Considered from this point of view and assuming the goal of full-scale application, we have just passed the midway point.

The development of solar cells in our generation was rather focused on how to make more efficient products at a lower cost. In the next phase we'll need to create systems and use solar cells as a core energy source capable of bearing 10 to 20 percent of Japan's electricity; and this is just about to begin.

What are your thoughts on the balance of energy sources and future prospects for solar power?

I believe in the combination of various energy sources; but considering issues such as pollution and the depletion of resources, it is obviously crucial for the future that Japan gradually shift from petroleum and nuclear power to natural energy.

Currently, applications for the sale of solar electricity have already exceeded 70 million kW, and it is estimated that the capacity of installed systems will reach 30 million kW by the end of 2015. We are even envisioning a future capacity of 100 million kW. Since the total capacity of Japan's power plants is somewhere in excess of 200 million kW, there is no doubt that photovoltaic energy will become one of Japan's core energies within a decade or so.

Please tell us what the key milestones are for the future of solar cells.

The largest problem facing solar cells has been cost. No matter how efficient they are, you'd be reluctant to install rooftop panels if they were prohibitively expensive, wouldn't you? The solution I am thinking of is low concentration photovoltaics (LCPV). There are some variations, but the basic idea is to focus a ten-fold concentration of sunlight on a certain spot and convert the energy to electricity. In a system aiming for a concentration ratio somewhere in the neighborhood of 1000 times, you would need to track the sun precisely, which means utilizing dual axis trackers to deal with Japan's cloudy climate. For LCPVs, however, single axis trackers would suffice. So, my next project will be LCPV.

How do you feel about Tokyo Tech as a place for study and research?

I sincerely feel that Tokyo Tech has given me more support than I could ever have dreamed of. This includes more than the outstanding research facilities. It also applies to the critical infrastructure that exists behind the scenes. The Institute has provided the kind of space and funding that we would never see anywhere else. The situation has been incredible, not only in the Environmental Energy Innovation Building (North Building 3), where my current laboratory is, but also in the Research Laboratory of Ultra-High Speed Electronics and in South Building 9 where I worked in the past. I am grateful to Tokyo Tech for making it possible for me to advance the state-of-the-art research I have been involved in.

So, you are still looking to the future?

If possible, I would like to live to see the world of 2050, where I believe that solar cells capable of producing 10 to 20 terawatts of energy will be a reality. Should I somehow manage to, I would be more than 100 years old [laughs].

I am eager to support the development of environmental energy as much as I can. I don't think it's time for me to rest just yet.

Please give a few words of encouragement to the students of Tokyo Tech.

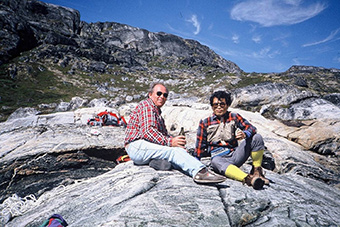

Konagai treasures the pictures he has taken

with the researchers around the world.

To become a world leader in research, first you need to:

- 1. Be passionate

- 2. Stick to your beliefs

- 3. Never be single-minded, but combine the technologies of other fields

- 4. Aim to develop systems after learning to develop devices

It is especially important to learn to combine the technologies of other fields. It is no good looking only at your own field of expertise. In my case, studying only solar energy wouldn't have provided me with an overall picture of energy sources. You will need to study and integrate fields such as wind and nuclear power.

Secondly, you need to:

- 1. Be able to make friends with people around the world regardless of their nationality, race or religion

- 2. Appreciate the traditions and food in the countries you go to

- 3. Never refuse an invitation

- 4. Be able to sleep anywhere in the world

I always had a hard time myself sleeping anywhere, though [laughs]. Anyway, I believe that being able to sleep anywhere requires courage. Please have pride and confidence in yourself, and jump out into the world.

Could you start by telling us about your area of expertise?

My main area of expertise is geology, and I've been involved in a wide variety of research on the history of the earth and life. My first subject of research was the geology of the Japanese Archipelago, and I spent almost 20 years completing it. Focusing on a hypothesis about the formation process of the Japanese Archipelago, I devoted myself to conducting high-pressure experiments to reproduce materials that may be present in deep Earth at University of Toyama and Stanford University. Then, about 20 years ago, I moved to Tokyo Tech. Although I continued with this work, I also started joint research with around 50 to 60 institutes from 30 countries. I collected a variety of samples from around the world to elucidate the history of the Earth and life.

Conducting geological survey in the Isua Greenstone Belt, Greenland in 1993

It is said that the ancestors of the human race evolved from apes around 6 to 7 million years ago. Since its emergence in the equatorial regions of Africa, the human race has spread around the world in the blink of an eye and has been evolving in a totally different way. I have attempted to systematize the conditions required for the emergence of life capable of developing the characteristics required to build and organize civilizations. I am currently involved in such research to finalize a grand theory that integrates everything from Darwinism to genome theory, and even astronomy.

You are currently involved in another major project, aren't you?

Yes. I'm also working on a project at the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI), which was established under the support of the World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI)1 of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. The project has been progressing actively since 2014 as a global-scale scheme that combines earth science, biological science and planetary science to solve the mysteries of the Earth and life.

The coexistence of ocean, atmosphere, and landmass is necessary for life, and the existence of landmass is especially critical for sustainability. Fortunately, there are more than ten thousand different surface environments available for this. These include ocean, atmosphere, and continents. We are taking a bottom-up approach to attempt to recreate the surface environment of the primordial earth by combining these different environments in a test tube. With a combination of this bottom-up approach and a top-down approach, we will be able to reconstruct environments similar to primordial earth. By the analysis of the genomes of microbes that adapted to pseudo-Hadean2 environments, I firmly believe that we will be able to track down the origin of life, humanity's greatest mystery.

It goes without saying that you are influential in the field of geology, but you also have influence in discussions of other fields as well. How did you gain such knowledge?

My style of research is to take a "bird's-eye view" of science. It is like overlooking the entire plain from above. The majority of researchers specialize in their own fields of expertise, but they cannot compete with experts from other fields when discussing a wide variety of topics. I saw some people trying to expand their horizons, but it seemed difficult for them to become competitive in fields outside of their own areas. Their knowledge tended to remain wide but shallow. I strived personally to study other fields to gain deep and broad knowledge beyond geology. Well, it was easier said than done [laughs].

Let me briefly explain how I mastered other fields. Taking biology, for example, there are 6,000 organic molecules. The key is not to memorize the name of each and every one of them, but to learn the most important key words. That is the first way to learn. The second way is to become friends with specialists in each field. Ask them to be your tutors, and study the basics of their fields thoroughly. By these methods, which I call "self-education" and "private tutoring," I obtained wide and deep knowledge in more than 50 different fields to discuss topics with various experts, sometimes engaging in fierce debate.

Tell us about your most memorable experience as a researcher at Tokyo Tech.

Five or six years ago, when Professor Makoto Oka was dean of the School of Science, they began to hold an annual event called the Christmas Colloquium; and I was asked to be the first lecturer. At that time, my opinions on global warming received both positive support and some criticism; but after I finished speaking, the entire audience, including the dean, understood my attitude toward research as a scientist with pride and dignity. They mentioned that they supported my attitude as it would fulfill my social responsibility as a scientist. I'll cherish their words throughout my life as there are no other words I could be more grateful to hear as a scientist.

Tell us your future plans and please give a few words to the students of Tokyo Tech.

I will retire as a member of the faculty, but I am planning to continue summarizing my studies. I have also received an offer to participate in an asteroid component analysis project related to planetary formation theory of the solar system. I'm also still making other plans for the future.

To the students, I would like all of you to have a sincere persistence in your studies and research. Real understanding requires far more than what you do when you are reading a newspaper. If you find a single item that you don't understand, you need to search through the literature and struggle. If you get absorbed in the struggle for understanding, you will feel a sense of accomplishment when you finally understand things, which is an experience of a lifetime. There are students who are seriously studying and willing to contribute to the world, however, regrettably there are also more and more students who misunderstand this point. I hope they will soon realize what I mean and find their own true purpose in life.

1 World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI)

The WPI program was initiated by MEXT in FY2007. The program aims to promote excellence in research by creating "globally visible" research centers where researchers from around the world will vie to come and conduct frontier research in a supportive and highly autonomous research environment.

2 Hadean

The Hadean is the geological period of time which began at the Earth's formation about 4.5 billion years ago and ended 4 billion years ago. It is assumed that the ocean and the earth's crust were formed, and that the earliest form of life appeared in the Hadean time.

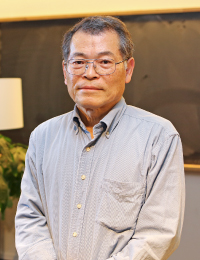

Makoto Konagai

- 1991Professor, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1981Associate Professor, Graduate School of Science and Engineering

- 1977Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Science and Engineering

- 1977Doctor of Engineering, Department of Electrical Engineering, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1972Bachelor of Engineering, Department of Electrical Engineering, School of Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1949Born in Kakegawa, Shizuoka prefecture

Shigenori Maruyama

- 2013Professor, Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 2004Professor, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1993Professor, School of Science, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 1989Associate Professor, College of Arts and Science, University of Tokyo

- 1981Postdoctoral researcher, Stanford University

- 1977Assistant Professor, University of Toyama

- 1977Doctor of Science, Division of Natural Science, Graduate School of Science, Nagoya University

- 1974Master of Science, Graduate School of Science, Kanazawa University

- 1972Bachelor of Education, Faculty of Education, University of Tokushima

- 1949Born in Anan City, Tokushima prefecture

The Special Topics component of the Tokyo Tech Website shines a spotlight on recent developments in research and education, achievements of its community members, and special events and news from the Institute.

Past features can be viewed in the Special Topics Gallery.

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.