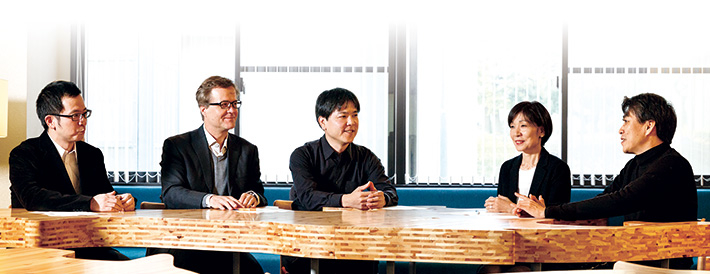

What thoughts occupy the minds of pioneering researchers? What attracts them to their field of study? What drives them forward? Institute for Liberal Arts Professor Masashi Shirabe spoke to four up-and-coming Tokyo Tech researchers about their work and their advice to students considering a career in research.

Shirabe:Hello everyone. Thank you for joining me today. I am sure that high school students, especially those preparing for their university entrance examinations, and undergraduate students thinking about graduate school would love to hear what goes through your mind as you work on cutting-edge research topics. Could you first tell us about your areas of study?

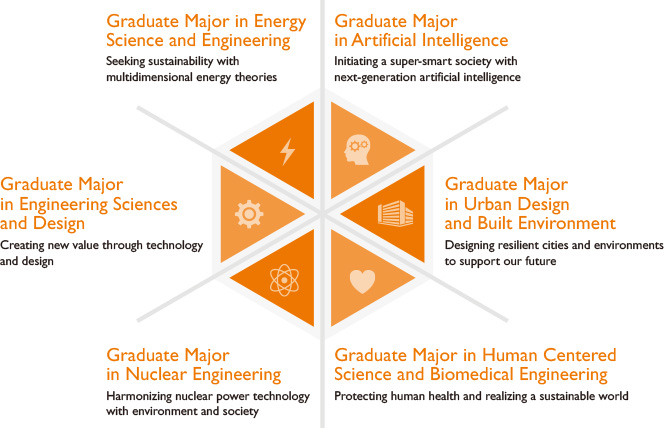

Hatano:I moved to Tokyo Tech from a company in 2010 because I wanted to make a societal impact with my research on fundamental physical phenomena. Specifically, I am working on the development of devices that control power conversion utilizing the unique physical properties of diamonds, and biological sensors with applications in healthcare.

Yamaguchi:I am a graduate of the first cohort of Tokyo Tech's 7th Academic Group. Currently, I am engaged in truly fundamental research on the mechanisms of gene expression and control. I have immersed myself in this field since I joined the lab in my 4th year of the bachelor's degree program. In addition to this, I am also involved in clarifying the mechanisms of the effects of drugs and other applied research in drug discovery, so I can say that my childhood dream of doing work of an altruistic nature has become a reality.

Mutsuko Hatano

Professor, School of Engineering

Yuki Yamaguchi

Professor, School of Life Science and Technology

Vacha:A central research topic in my lab is the clarification of properties and processes in organic and polymeric materials at the nanoscale level. Among these, I focus on organic semiconductor materials used in solar cells and organic electroluminescent materials. By utilizing a special method called single-molecule spectroscopy, which analyzes the light emitted by individual molecules, we can clarify structures and characteristics at the nanoscale level.

Jinnouchi:As a member of the Japanese group of the ATLAS Experiment, a project involving the combined efforts of particle physicists around the world, I am working to identify unknown particles using the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world's most powerful particle accelerator, located at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). In 2013, the LHC was used to confirm the existence the Higgs boson, an elementary particle predicted by Peter Higgs, a physics Nobel laureate. My research focuses on attempting to identify supersymmetric particles derived from the theory of supersymmetry.

Martin Vacha

Professor, School of Materials Science and Engineering

Osamu Jinnouchi

Associate Professor, School of Science

Freedom, and the chance to be the first to discover something new

Shirabe:What is it about your research that gives you the greatest satisfaction?

Jinnouchi:If we can find the supersymmetric particles we are looking for, we will have defied conventional wisdom. That would mean completely rewriting the physics textbooks. There is no challenge more exciting than that!

Vacha:My motivation is very similar. It is exhilarating to have the opportunity to confirm the properties of materials that have not been discovered yet. Most of this kind of work can only be achieved through research at universities. The process is by no means easy, and obstacles abound. However, experiencing the joys of discovery and sharing them with my students through teaching is a real pleasure.

Yamaguchi:Of course, it is very satisfying for a researcher to be the first to discover something new. For myself, one of the major attractions of research at university is the freedom to pursue our interests — wherever they may lead. While focusing on one topic, for example, we sometimes discover something altogether different quite unexpectedly, which then leads to even more interesting directions in research. Such flexible shifts in research topics are possible at university, while the goal-oriented research at companies usually requires one to stick with a single line of inquiry. This is one great advantage of conducting research at a university.

Hatano:I came here from an industrial research institute, and I fully agree. The freedom at university allows you to see where the research leads you rather than having to follow one specific, pre-determined route. Because of this, consequences can rapidly change, and it is often at these times of change that discoveries are made. We can act according to these consequences, and work with specialists in other fields when we see fit. A university researcher putting together a study is like a conductor compiling an orchestral performance. And let me tell you — it is not nearly as stressful as research at a company.

Shirabe:I don't think research at universities is that easy either. [laugh]

Hatano:Of course, we encounter a wide range of difficulties in a university setting as well. However, because we exercise control over our own decisions, there is less stress. As Professors Vacha and Jinnouchi pointed out, we have the chance to be the first to discover something new. Regardless of whether the world reacts, we know that we "own" that discovery [laugh].

Fundamental and applied research are equally exciting

What research is useful?

Shirabe:Generally, when people think about research in the field of science and technology, they think about applied research directly connected to commercialization, research that leads to "concrete answers." Applied research seems to be more popular than fundamental research among students, too. However, after hearing Professor Ohsumi emphasize the importance of following your own interests in fundamental research at his Nobel Prize press conference, I think more people realized the value of such research, even though it may not lead to immediate conclusions. What do you think?

Hatano:I agree, and I think it is great. Industry does not always expect universities to carry out applied research that leads to commercialization. They also greatly value fundamental research, which is not easily executed under corporate research structures.

Vacha:I often hear students saying that they are interested in research that will be immediately "useful" to society. Some 4th-year students in my lab have said that they want their research to have an impact after one year, but that kind of goal is unrealistic.

Hatano:As a company researcher, I worked for many years on research that was seen as "useful." However, very little of that work actually led directly to commercialization.

Vacha:Yes. I really want students to understand the joy of doing fundamental research.

Yamaguchi:I think students can easily understand the meaning of research if they see its direct application in society. I was like that too. Until I understood the true meaning of research, I tended to concentrate on applied research because it was easier for me to see its connection to the real world. Although fundamental research is not as clear in this sense, it gives you the feeling that you are finding answers to puzzles that no one has ever tried.

Vacha:You will not know the joy until you try.

Yamaguchi:That is why joining my research group is a two-step process. I try to attract students with applied research that is easy for them to understand, and then invite them to experience the joy of fundamental research after they have joined.

Shirabe:Interesting. How do students choose the topic of their graduate thesis? Do more people lean towards applied research?

Yamaguchi:Not at all. Once they experience both fundamental and applied research, they realize that fundamental and applied research are equally exciting.

Hatano:I agree. I feel that there is no real need to separate academic research into fundamental and applied.

Jinnouchi:I feel the same way. Fundamental and applied research are not separate, quite the contrary. They are always somehow connected. That is another one of the joys of research.

What should we do to be more competitive?

Shirabe:I feel that Tokyo Tech has created an excellent environment for researchers, but global competition in the field of science and technology is fierce. We cannot afford to rest on our laurels. Can you share your views on how we can be more competitive?

Hatano:It is essential to promote cross-disciplinary interactions, something that Tokyo Tech set as a major focus in its research enhancements in 2016. My research on biological sensors would benefit greatly from collaborative work with medical specialists and researchers specializing in proteins at other universities. It is very difficult today to create new value without integrating research fields. In this sense, I feel that Tokyo Tech's research enhancement efforts are very significant, and that this issue requires a nationwide effort if we are to be more competitive globally.

Vacha:I think it is necessary to reform the doctoral program system in Japan. The country needs to improve financial support for researchers with doctoral degrees. If the system more closely resembled that of the United States or Europe, where researchers are paid a salary to work on individual projects, the number of outstanding students leaving university after a master's degree would decrease. This would boost the research capabilities of Tokyo Tech, too.

Shirabe:Do you think students feel that aiming for a doctoral degree puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to finding a job?

Jinnouchi:Perhaps some do, but it is far from true. Many doctoral program graduates are working actively at private companies.

Yamaguchi:That is particularly the case in the field of chemistry, where employment opportunities are vast.

Vacha:Most graduates join private companies, while some remain in academia. In fact, while the number of postdoctoral researchers has been decreasing in the United States and Europe due to budget cuts, the number has remained stable in Japan.

Hatano:My previous corporate employer hired many researchers with doctorates. With the broad perspectives in a variety of fields you bring to the table, you are highly valued wherever you go.

Jinnouchi:I have heard researchers at private companies saying the same thing. They believe that individuals with doctorates are highly regarded in terms of both theoretical thought and project management.

Hatano:On the global stage, researchers with doctorates are very common. I suspect that Japanese companies will increasingly require such researchers in the future.

Ultimately, you determine your future direction.

Shirabe:Finally, I would like to ask if you have a message for young students who would like to become researchers in the field of science and technology.

Hatano:Researchers these days are less sure about what to investigate. They are expected not only to identify topics, but also create new value and design future society. In order to realize such dynamic research, it is essential to cooperate with other researchers specializing in different fields. That is why Tokyo Tech created the Institute of Innovative Research (IIR), a structure that will undoubtedly revitalize research activities and greatly benefit students who decide to become researchers. Faculty members also utilize this research environment to push the limits of individual students. We all hope to have many outstanding students joining us here at Tokyo Tech.

Yamaguchi:I have experience counseling high school students about their future careers, and I noticed that many of them did not know if they wanted to join the 7th Academic Group at Tokyo Tech or the faculty of medicine or pharmacy at another university. They really want to be engaged in life science research, but it is easier to visualize their future path if they choose medicine or pharmacology, a choice that also appeals to parents and teachers. Many students simply do not know which is best for them. Of course, it is important to discuss this with their families and teachers. However, my message to students is that ultimately, it is you who determines your future direction. Any direction you choose has its challenges. Whatever you do, do it with all your effort. I want young students to find what they really want to do and open the door to their future. Fundamental research, applied research, collaborative research — all of this is possible at Tokyo Tech, a diverse environment that responds to every student's needs and expectations.

Vacha:True interest is the best motivator for any researcher. It is important for individual students to first find what truly interests them. After entering university, it is also important for students to discover their own, unique research topic. If they can do this, the doors to the future will open up. University provides an open environment where one can fully pursue research that nobody else has ever worked on. There is nothing more exciting than that. Our graduates often say that, although they find research at a company motivating, the Tokyo Tech environment was unparalleled in terms of the pure pleasure of research.

Jinnouchi:The other day, my research group had a reunion for the first time in 20 years. All my classmates who joined companies after acquiring their master's degrees said that the two-year master's program at Tokyo Tech was the best time of their lives. It is an unforgettable memory, a special chapter of youth in their book of life when they could wholeheartedly focus on their research.

Shirabe:So that means that those of us who stayed to carry out research at university are still in our youth, right?

Jinnouchi:Yes, of course [laugh]! For the past 20 years, science and technology has progressed at an extraordinary pace, and breakthroughs are made every year. While global competition among researchers continues to intensify, studying and conducting research at Tokyo Tech means being involved in truly cutting-edge research activities. We hope many young students with big dreams enter Tokyo Tech.

Shirabe:Thank you for your time everyone.

Jinnouchi Group

Associate Professor Osamu Jinnouchi

Martin Vacha Laboratory

Professor Martin Vacha

Yamaguchi Lab

Professor Yuki Yamaguchi

Hatano & Kodera Laboratory

Professor Mutsuko Hatano

Shirabe Laboratory

Professor Masashi Shirabe

Published: November 2017

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.