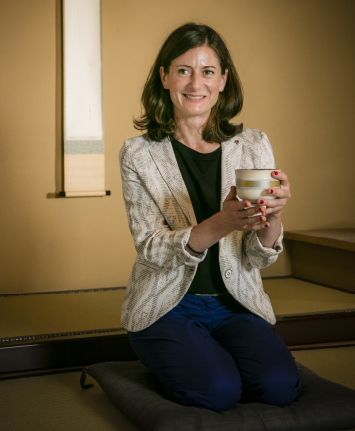

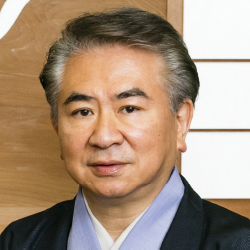

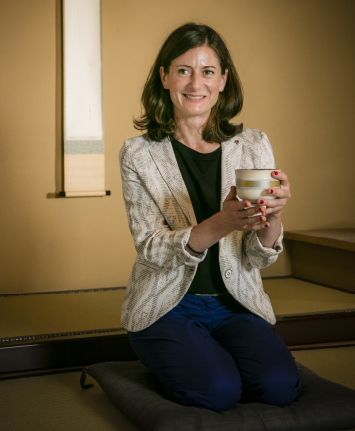

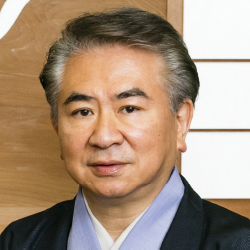

Associate Professor Céline Mougenot proposes future-oriented devices that rely on user-centered design. Grand Master Sojitsu Kobori carries forward the spirit of Japanese tea ceremony through a deep "understanding of the guest's feeling." The two shared a peaceful moment to contemplate how they turn awareness of human emotion into practical and artistic expression.

Date: July 13, 2016 at Enshu Sado School in Shinjuku, Tokyo

Space: A dimension of communication deeply rooted in Japanese tradition

Kobori:Dr. Mougenot, what does Japanese tea ceremony mean to you?

Mougenot:Completely organized methods and movements, which I think are also very common in traditional Japanese dance and martial arts.

Kobori:Yes, that is very perceptive. Enshu Kobori, the founder of our tea school, practiced the art of tea with the spirit of wabi, established by Sen no Rikyu, and developed it into buke sado, a form of tea ceremony practiced by Edo period warriors. He added beauty, brightness, and affluence to the spirit of wabi-sabi to create an aesthetic of grace, simplicity, and objective beauty, which is known as kirei sabi.1 The way of tea practiced by warriors emphasized the spirit expressed through our bodies, much like martial arts do. The ceremony itself includes elements of Japanese classical arts such as Noh, which prioritizes space and breathing.

Mougenot:What do you mean by space?

Kobori:Different cultures view space differently. The Japanese have developed a way of recognizing space between individuals when communicating. This space does not emphasize distance per se, but instead expresses a humble respect for others.

Mougenot:That must be the cluster system we set up for basic research on TSUBAME.

Kobori:During a tea ceremony, when facing a guest, the host first places a fan in front of him or herself to set a boundary with the guest, and then bows. The host then removes the fan to eliminate the boundary. With this, both are ready to enjoy conversation. This setting of a boundary is also a way of expressing respect for the guest.

Mougenot:Europeans and Americans shake hands and hug when they meet!

Kobori:When you and I are talking, we sometimes continue without pauses, and at other times take a moment to collect our thoughts before continuing. That moment — or space — allows a certain calmness, a tranquility that is emphasized in tea ceremony as a sign of respect and a means of enhancing the time spent together.

As you noted, the spirit of Japanese martial arts is very similar to that of tea ceremony. The space during a tea ceremony resembles the engagement distance in a kendo bout, or the warm-up ritual that precedes every sumo match. These spaces or intervals are not intended to express hostility, but rather to show respect for the opponent.

Mougenot:That is a wonderful way of thinking.

Integrating function and affectivity in engineering and tea

Kobori:In tea ceremony, I focus on the happiness of my counterparts. I strive to create an atmosphere suitable for individual guests, to serve delicious tea, and to ensure enjoyable conversation, all designed to provide a pleasant experience.

Mougenot:I carry that same spirit in my research. In the fields of affective engineering2 and interaction design, I apply scientific approaches to research the emotional aspects of individuals who use smart phones and other communication devices. Product development in engineering often prioritizes function. However, the primary feature of my research is the focus on affectivity, on the joy and excitement people experience when using these devices. To achieve this, I have expanded beyond the boundary of engineering to include art, psychology, sociology, and marketing in my work.

Kobori:Function and affectivity, you say. These are also important themes in tea ceremony. For example, I design tea bowls. Of course, when I view the tea bowl as a tool for the ceremony, I strive for a perfect design. However, I entrust the user of the tea bowl to complete the final step of perfection.

Mougenot:How do you do that?

Kobori:A tea bowl is used to prepare tea for a guest, but the emotion and spirit of the individual user is the final touch to each bowl. In fact, the tea bowls I design are sometimes valued by their users in very unexpected ways, which is always a pleasant surprise. May I ask what scientific approaches you utilize when researching people's emotions?

Mougenot:It is, as you say, scientific research, so I begin by collecting plenty of objective data. Data on facial expressions, blood pressure, perspiration, and the like. I then use computers to analyze this data and attempt to clarify how people use their brain, body, and senses when they come into contact with different products.

Kobori:How do you apply the findings of your research to society?

Mougenot:Modern society has reached a stage where all sorts of things are virtualized. Instead of writing letters by hand, for example, we have come to use email almost exclusively. These developments have greatly reduced opportunities for us to use our bodies and senses. Individuality has been lost. Computer fonts do not have individuality. My research aims to develop devices that deeply appeal to our bodies and senses, and provide us with more enjoyment during use.

Kobori:A kind of thoughtful hospitality provided by devices. That is very interesting.

Mougenot:What impresses me is that tea masters understand their guests' emotions so thoroughly. It seems they are able to read them with great accuracy and tend to their individual needs, only without any help from data or computers utilized by scientists.

Kobori:We use the knowledge we accumulate from experience. By carefully considering the feelings of others, we are sensitive to the slightest changes in facial expressions and movements of the mind. While making tea and conversing with our guests, we remain highly aware of the mood. I have developed this affectivity through the practice of tea. One important barometer we use to understand people's feelings is the space I mentioned earlier.

Mougenot:Space and mood. I am learning the depth of many Japanese concepts today.

Kobori uses Saint-Louis crystal for the tea to show hospitality to his French guest.

Designing pleasure through attentiveness to others

Mougenot:I know there are many specific rules in tea ceremony. Can we enjoy it even if we do not know these rules?

Kobori:Of course, you can. While these rules are important, it is more important to enjoy the tea itself. When we decide on wine at a restaurant, we first ask the sommelier for a recommendation. We then taste the wine, and enjoy the food and company of those with us. Basically, tea ceremony is not any different.

Mougenot:If that is the case, then I am confident I can enjoy tea ceremony too!

Kobori:I have no doubt. Attentiveness to others around you is important, and these rules exist to make that attentiveness easier. In tea ceremony, we also respect the tools we use. We hold the tea bowl with our hands, feel it with our lips, and enjoy the different textures of pottery, lacquerware, glass, and wood. This may be a unique Japanese way, developed over time, to show respect to the items we use daily. These tools may also have cracks and blemishes. We revere such defects and, through conversation with our guests, find pleasure in turning these seemingly negative characteristics into positive ones.

Mougenot:That's a very interesting perspective! When we design devices, texture is also an important element. Traditionally, engineering has focused on realizing advanced technology in products, with little attention paid to how people actually use these products. Thankfully, this is changing. One reason for the rapid increase in smart phones and tablets is that we can feel the texture of the product and enjoy the intuitive movements we make with our fingers. I believe we have reached a point where designing a pleasurable user experience is as important as developing the functions of a device.

Kobori:Designing pleasure. I agree with you. The harmony of people, tools, hanging scrolls, flowers, conversation, the sound of boiling water, and making tea — these all contribute to the grace of a tea ceremony. For people whose lives are shaped by information overload and lack of time, spending a moment in the serene, dignified atmosphere of a tea ceremony is a good chance to reflect on the importance of simplicity, and on oneself.

Mougenot:Emotional exchange between the host and guests to create a comfortable atmosphere. That sounds like affective engineering. It is a wonderful surprise to learn that the way of tea, with its long history, is similar to the research I engage in. I cannot help but feel that there are many aspects of tea ceremony that I agree with. Knowing that the concept of up-to-date engineering design so closely resembles the thoughtful hospitality you extend to your guests provides me with great inspiration, which I will surely share with my students.

1 Kirei sabi

Haber and Bosch established the first method of ammonia synthesis that directly synthesized airborne hydrogen and nitrogen. This is often called the Haber-Bosch (HB) process. Haber received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his research on ammonia synthesis research, and Bosch received the prize in 1931 for the high pressure reaction process he developed.

2 Affective engineering

First established in Japan, affective engineering has expanded throughout the world. This field of study focuses on the measurement of emotional response and the application of the results of such measurements to the process of design. Based on the perspective of engineering, affective engineering seeks to clarify people's sensibility from a wide range of approaches, including psychology, sociology, aesthetics, semiology, and marketing.

Céline Mougenot

Associate Professor, School of Engineering

- 2016Associate Professor, School of Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 2011Associate Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 2009Research Associate (JSPS Research Fellow), University of Tokyo

- 2008Doctor of Engineering, Arts et Metiers ParisTech

- 2005Master of Industrial and Product Design, Universite de Technologie de Compiegne

- 2001 - 2005Dassault Systemes

- 2001Master of Mechanical Engineering, Institut National des Sciences Appliquees (INSA Lyon)

Sojitsu Kobori

The 13th Grand Master of the Enshu Sado School

- 2011Senior Director, Kobori Enshu Kenshokai

- 2001 -present The 13th Grand Master of the Enshu Sado School

- 1979One year of training at a Zen temple

- 1979Bachelor of Arts in Law, Faculty of Law, Gakushuin University

- 1956Born in Tokyo.

Kobori has published several books. In his newest work, "Five Senses in Japan," he describes Japanese aesthetic perception from the viewpoint of tea ceremony while taking into account the five senses, which have been valued in Japan since ancient times.

In 2014, "My Father is the Grand Master," a documentary featuring Enshu Kobori, was screened in Japan and abroad.

The Special Topics component of the Tokyo Tech Website shines a spotlight on recent developments in research and education, achievements of its community members, and special events and news from the Institute.

Past features can be viewed in the Special Topics Gallery.

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.