In October 2017, Associate Professor Mikiko Tanaka and colleagues published the study in Nature Ecology & Evolution that attracted attention from researchers all over the world. This paper overturned conventional theories.

In Tanaka's field of evolutionary developmental biology, or "evo-devo" for short, a major topic of research is to understand how various organisms have evolved by changing forms, and the transition of their development programs.

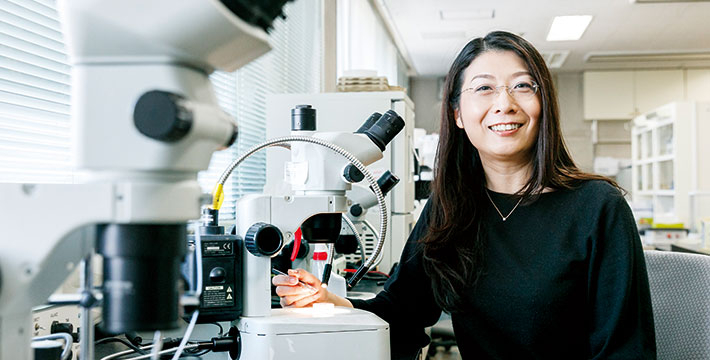

Mikiko Tanaka

Associate Professor , School of Life Science and Technology

1993: Graduated from the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Osaka City University. 1998: Completed Ph.D. at the Department of Biology, Graduate School of Science and Faculty of Science, Tohoku University. Worked as overseas special research fellow at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (1998 London University, 1998-2003 University of Dundee), Uehara postdoctoral fellow (Oregon University). 2004: Joined the Department of Biological Science, Graduate School of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Tokyo Institute of Technology as an associate professor. Current position since 2004. Member of the Japanese Society of Developmental Biologists, The Zoological Society of Japan, The Molecular Biology Society of Japan, The Society of Evolutionary Studies, Japan, and has served as an officer, councilor, and in other roles. Holds a Doctor of Science degree.

Laboratory

Researcher Profile

Recommended books

I think students of high-school-age, rather than just studying, should read lots of books on any animals that they find interesting. Read what interests you, not books that I would recommend.

All vertebrates living on land, including humans, evolved from creatures that came from the ocean. In the Late Devonian period about 350 million years ago, the first vertebrates to adapt to land were amphibians, and it is believed that their ancestors were primitive, now-extinct fish with fin-like limbs and belonging to the class Sarcopterygii. The class Sarcopterygii contains coelacanths, lungfish, and all tetrapods.

Cartilaginous fish such as sharks and chimaera, which are used as models in Tanaka's lab, show characteristics from their ancestors.

"In my lab, we have been studying the developmental mechanisms responsible for the evolution of fins and limbs. Forelimbs and hindlimbs of animals evolved from pectoral and pelvic fins of ancestral fish. Cartilaginous fish such as sharks and chimaera occupy critical phylogenetic positions and are good models for examining the evolutionary processes of vertebrate limbs." (Tanaka)

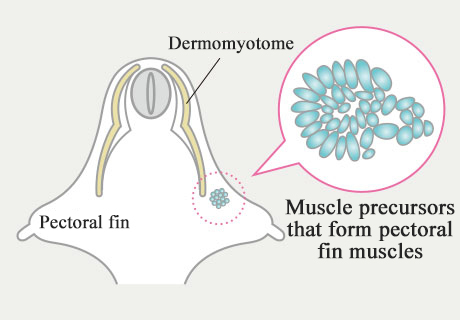

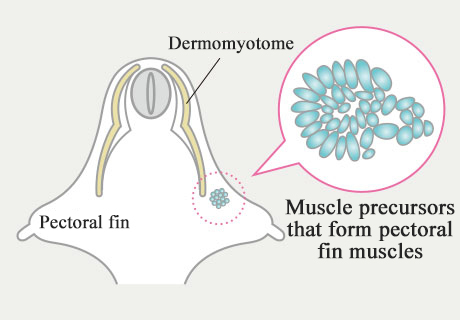

In amniote embryos, skeletal muscles are derived from epithelial cell layers called the "dermomyotome." At trunk levels, dermomyotomes extends ventrally to form body wall muscles, whereas at limb levels, ventral dermomyotome generate a cell population called "migratory muscle precursors" that migrate distally into the limb bud. Their study revealed how the muscles for pectoral fins and pelvic fins of cartilaginous fish are formed.

"It was believed that the muscles of the paired fins (collective term for pectoral and pelvic fins) of cartilaginous fish were derived from the epithelial dermomyotome directly extending into the fin bud, and not migratory muscle precursors. This theory was proposed by an English zoologist in the 1930's, and in the 2000's, a paper supporting this theory was published in Nature, making it an established ‘theory.' However, some researchers, myself included, had doubts about this theory." (Tanaka)

3D image of the molecular distribution expressed

in the migratory muscle precursors of sharks

Tanaka and colleagues then used embryos of the catshark, a cartilaginous fish, to verify the mechanism of paired fin muscle formation. It was found that the paired fins of the catshark are formed from cells with characteristics of migratory muscle precursors. This discovery overturned the existing understanding of biology and elicited many inquiries from abroad.

"Although the cells were re-aggregated as soon as they left the dermomyotome, from the molecular evidences, sections created by Okamoto-san and subsequent 3D images, we confirmed that the cells were muscle precursors separated from the dermomyotome. This discovery showed that both bony and cartilaginous fish develop their appendicular muscles via a shared mechanism. " (Tanaka)

Illustration of muscle formation

in the paired fins of a catshark embryo

Cloudy catshark and elephant shark used in the study.

For the blue elephant shark (right), the cartilage is stained.

Through research using catshark embryos, Tanaka's team revealed that the balance of the anterior (thumb side) and posterior fields in fin buds shifted as evolution progressed from fins to limbs. They further found that the genomic sequence controlling the expression of the causative gene changed. They have also studied the origins of paired fins using cephalochordates, which are a more primitive chordate with no paired fins.

"There are various types of living things on the earth. How did such diversity evolve through the history of evolution? Why did fins evolve into limbs? What was the program for generating arms and legs at the correct positions? Why are there many different limb shapes among animals? I want to approach each of these questions in evolution." (Tanaka)

Tanaka first learned of development and evolution research when she was a high school student.

"In a high school class, I saw a video about how a human fetus developed from a fertilized egg into a baby, and felt that this was what I wanted to study. I didn't think about becoming a medical doctor, I wanted to become a researcher who operates on her own. But, in high school, I wasn't good at biology because it was just about memorizing... Actually, I'm still not good at memorizing (laughs)." (Tanaka)

As an undergraduate, she engaged in research on the evolution of sea squirts, and in graduate school, she studied the morphogenesis of limbs using chickens. The foundation of the present Tanaka Lab was laid through later research in the UK and the United States that incorporated both evolution and morphogenesis.

"I've always felt that I should do what I care about, because you only live once. So I'm enjoying what I do now. However, research is not something I can do alone. I am supported by Tokyo Tech and by the hard work of great students, and collaboration with outside researchers, including overseas, is essential for research. Our study on the development of paired fin muscles using the catshark was done with teams from the University of Tokyo, RIKEN, and the life science research institute CRG (Centre for Genomic Regulation) in Barcelona, Spain." (Tanaka)

Since there are many approaches to research, joint research can extend beyond the limits of what any individual can do, which is thrilling.

Tanaka explains, "Rather that researching something because it's useful, I want to research themes that I find interesting, themes that I wonder about."

"For example, I am interested in whether forms change according to the surrounding environment even with the same species. There are birds that have different color feathers in summer and winter; ants have different forms according to roles like queen ant, soldier ant, and worker ant. Influenced by the environment, what development programs control morphological changes like those seen in these examples? My research interests are not immediately helpful to the world, but I think that knowing the fundamental rules of evolution and life is important in order for science to progress." (Tanaka)

Tanaka's team is utilizing the latest genome analysis technologies to pursue the mysteries of evolution. Their research using cartilaginous fish as models is technically challenging and unique in Japan, and it has attracted international attention due to its recent discovery.

Tanaka and her students continue to work according to the philosophy, "Don't worry about what you're good at or not good at. Do what you enjoy. The important thing is to have fun doing research!"

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.