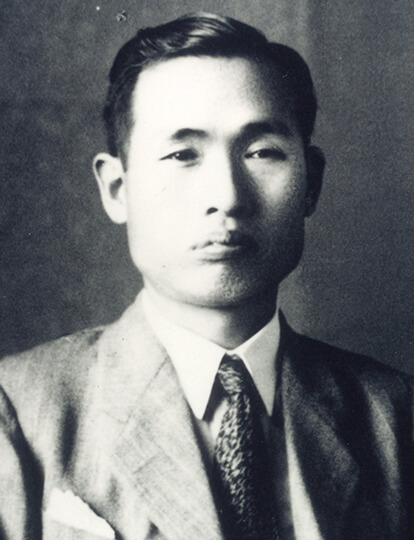

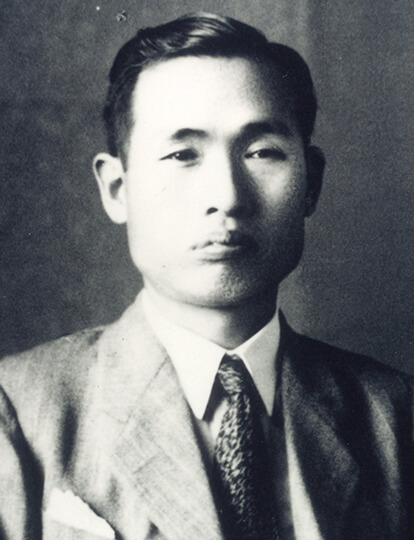

There was a man called the "Father of Television" in Japan, who developed the world's first practical electronic television in 1926. He was Dr. Kenjiro Takayanagi (1899 - 1990) and a graduate of the Tokyo Institute of Technology. Invited to the NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) Technology Research Center, he led experimental television broadcasting to success in 1940. His endeavors in television continued after World War II and played a significant role in official television broadcasting launch in 1953, and the development of Japan's first TV set, as well as VTR and videodisc products.

Monochrome TV, about half a century ago

(Takayanagi Memorial Hall)

His legacy in the most important medium of the 20th century - both in its hardware and platform - is too great to forget. Let's retrace the path of how he became intrigued by the world of communication and was inspired to his achievements. The following article was prepared by Professor Hiroichi Yanase (the Institute for Liberal Arts).

Born in 1899 in the present Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, Takayanagi was a great fan of science even as a child. In particular, his passion for "communication" started in his elementary school days, inspired by two incidents: a wireless communication demonstration conducted by the Navy and the sinking of the Titanic, which was wirelessly broadcast globally. Pursuing his interest, he enrolled in Affiliated School for Technical Teacher Training, Tokyo Higher Technical School (then located in Kuramae*) and met Professor Kounosuke Nakamura, his mentor and the future first president of Tokyo Tech, who said:

"Don't follow today's trends. Discover technology that will benefit your country decades from now. Steadily walk your path to developing what the world will want in the future, in 20 years."

Dr. Kenjiro Takayanagi

Those words became a compass to Takayanagi, who embarked on searching for a research theme in the field of telecommunication while working as a technical high school teacher. He even learned German and French at night schools to read through technical magazines published in countries such as the U.S., U.K., Germany, and France. In an age long before the Internet, this man in the early twenties was already looking toward the world, actively sourcing global information for more accurate results.

- *

- Located in the southwest of Taito-ward, Tokyo and the origin of Tokyo Tech

When he was still seeking his path, Westinghouse Electric Corporation in the U.S. opened a radio station in Pittsburgh, "broadcasting" music or talks, which many people could receive simultaneously. Japan did not have any radio station yet, and the reasonable decision would be "to start research in radio." However, Professor Nakamura's compass in his mind said otherwise: "Aim beyond the radio!"

Something "beyond the radio" Takayanagi envisioned was "an invention to telecommunicate visual images," and he named this idea the "wireless far-sight method." His thought at that time went, "invent what no one knows but would make everyone happy if they had it" and he started exploring a method to turn this idea into reality.

His vision became clear as a picture one day when he was reading a French magazine article entitled "Television," which showed an illustration of a woman singer singing in something like a picture frame installed on the radio receiver. Now convinced that his "wireless far-sight method" was this "television," he renewed his determination to develop this technology earlier than anyone else in the world.

The world's first successful imaging via a Braun tube prepared for the aborted Olympic games

Takayanagi Memorial Hall established

at Shizuoka University Hamamatsu Campus

However, the wheel of fortune can work strangely. On September 1, 1923, a devastating earthquake hit the Kanto region, destroying the Tokyo Higher Technical School buildings, including his workplace, which forced him to return to his hometown, Hamamatsu. He started working as an assistant professor at the newly-established Hamamatsu Higher Technical College (presently the Faculty of Technology at Shizuoka University) the following year, when he was 25.

There he met someone who would give him a chance to develop television. That was Sokichi Sekiguchi, the first president of the college, to whom Takayanagi suddenly declared his dream upon his arrival at school.

"You can watch a Kabuki performance taking place in Tokyo from Hamamatsu. That's what I want to make happen."

He might have looked like a mere "visionary," particularly when there was no presage of such a thing in Japan and NHK had not yet even opened its radio station (which it finally did the following year). President Sekiguchi himself being not an ordinary person, he answered, "All right. I'll get a budget from the Ministry of Education. Start your research at once." He gave a powerful boost to his motivation.

Excellent research involves a sufficient budget and a boss who is quick to make decisions. Probably well aware of this, Sekiguchi was fascinated by the reasoning and creative power behind the "wireless far-sight method" idea.

However, his research soon came to a standstill. President Sekiguchi died from illness, and the budget for this unrealistic project was frozen. Then, what did he do? Never daunted, he contacted Shibaura Engineering Works (presently Toshiba Corporation) in Tokyo and, proposing an "Industry-academia collaboration" all alone, he successfully obtained an agreement.

At this time various nations had started the development of television, based on either of two scanning methods: mechanical and electronic. The mechanical method used two round disks with many little holes arranged in a spiral, which are rotated to send and receive images in units called "frames", while the electronic system employed a large vacuum tube (Braun or cathode ray tube).

Seeing more potential in the electronic method, Takayanagi chose it over the mechanical counterpart, which had taken the lead in development. His intensive research began.

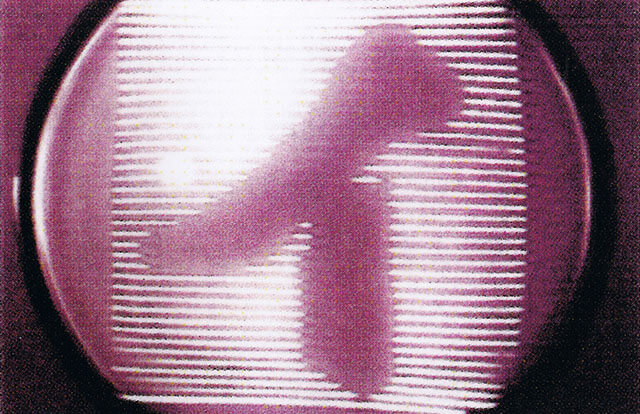

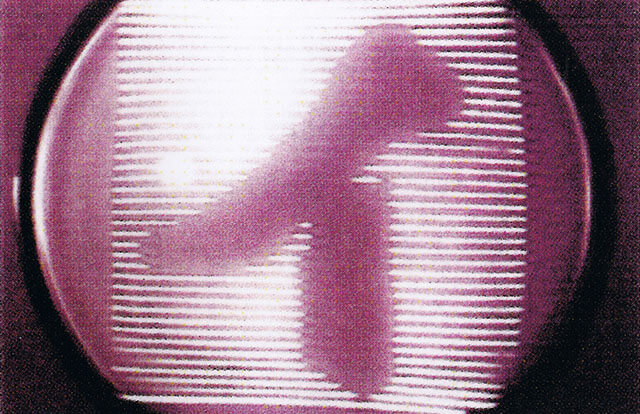

On December 25, 1926, at the lab of Hamamatsu Higher Technical College, the 27-year-old scientist succeeded in scanning an image with the aforementioned mechanical disk, displaying it on the electronic cathode ray tube. It was the moment when an image was transmitted to a cathode ray tube for the first time. The image sent was "イ," the first letter of the old Japanese alphabet, and this was the beginning of Japanese television. In 1930, he succeeded in reproducing even clearer images on the tube.

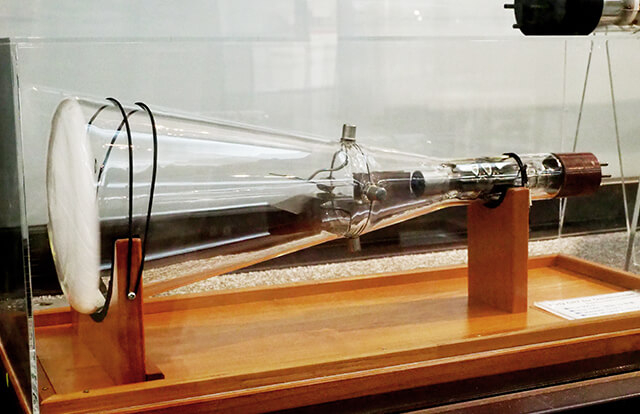

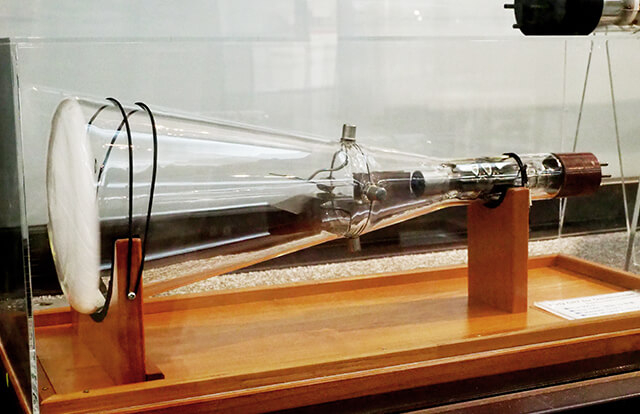

The cathode ray tube (left) Dr. Takayanagi used in experiments and the character "イ" (right)

imaged by the television technology in those days (Takayanagi Memorial Hall)

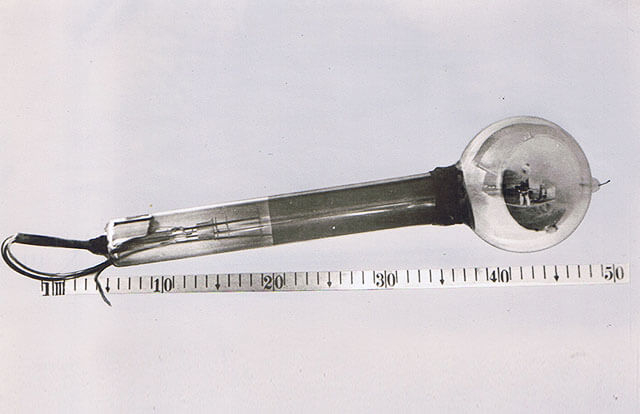

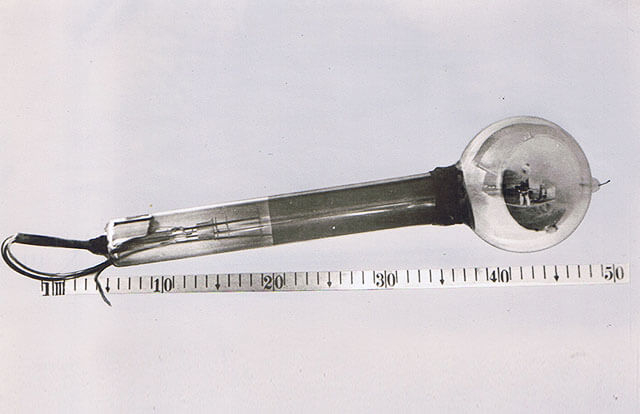

However, Takayanagi's television was not entirely "electronic" at this stage, since its imaging tube (equivalent to today's video camera) was mechanical. Struggling to create a practical electronic imaging tube, he decided to visit Dr. Vladimir Koz'mich Zworykin at RCA (Radio Corporation of America) in the U.S. The electronic Iconoscope imaging tube invented by Dr. Zworykin was just marvelous, capable of creating outstandingly clean pictures, which amazed Takayanagi and galvanized him to eventually develop his original Iconoscope.

Takayanagi's Iconoscope (Takayanagi Memorial Hall)

When NHK started preparing for television broadcasting, Tokyo had been chosen as the host of the 1940 Olympic Games, and the nation decided to start its broadcasting at the same time. Upon being invited by NHK, Takayanagi joined its technical research team. Pursuing its goal, the team constantly refined the cathode ray tube and Iconoscope, finally succeeding in experimental broadcasting using relay vehicles. The time was ripe for the first Japanese electronic television system.

Unfortunately, the political situation in those days was not favorable for this innovation. In 1937, the Sino-Japanese War occurred, which drastically changed Japan's international status and forced the Olympic Games to a halt, cornering the nation to the Pacific War; and the television project was suspended. For his renowned expertise as a world-class communication engineer, Takayanagi was summoned to military duties to develop radar and night vision equipment as well as radio wave applications in weaponry.

Another legacy of Takayanagi: researcher spirit and entrepreneurship

After the war, what awaited him was expulsion from public office due to his involvement in the military, which prohibited him from working at NHK or national schools. However, there was no reason for the private sector to miss this opportunity. He was invited by Japan Victor Corporation, where he devoted his efforts to establishing Japan's original television system through collaboration with Sharp, Toshiba, and even NHK.

In 1953, NHK started television broadcasting. One of the first set of programs aired was a Kabuki performance, as he had once told President Sekiguchi at Hamamatsu Higher Technical College that people could watch one while staying at home far from Tokyo. It was the moment his dream came true.

Japan's original TV developed by Takayanagi and his team was manufactured and launched by Sharp in the same year. The price was high — almost 200 thousand yen — equal to the annual salary a university-graduate new employee would receive in those days. Only 866 viewers subscribed to NHK's broadcasting. Television was a luxury item then, but this had completely changed by 1964, eleven years later and the year of the Tokyo Olympics, when nearly 90% of the population owned a television set.

Dr. Takayanagi's bust and IEEE Milestone Award Winning Memorial

(Shizuoka University)

Even after his success in television, his passion for innovation never faded. Instead, it expanded to cover VTR and video discs, contributing to the development of television technologies. His achievements were highly commended by various parties, including the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) in the U.S., who certified his work as a historically significant accomplishment in the electrical and electronic technical field.

Now, what was behind his invention of television in 1926, at the age of 27? It was the words of Professor Nakamura, the first president of Tokyo Tech: "Look to the future and turn something currently not available into reality," which inspired him. It was also what President Sekiguchi at Hamamatsu Higher Technical College said: "Scientists should fully exploit freedom and creativity, whereas funding is my job," which empowered him.

For someone related to Tokyo Tech and engaged in research and development as well as entrepreneurship in the science and technology fields, it is encouraging and motivating to learn how our first president inspired a graduate, who would eventually give birth to the most significant medium of the 20th century.

Cooperation: Takayanagi Memorial Hall, Shizuoka University Hamamatsu Campus (Japanese Site)

Hiroichi Yanase

Graduated from the Faculty of Economics of Keio University, and joined Nikkei McGraw-Hill (present Nikkei BP). After accumulating various experiences as a reporter for the "Nikkei Business" magazine, editor for specialized magazines, developer of new media, and book editor, engaged in content planning and advertisement production as the producer of the "Nikkei Business Online" series. As of April 2018, assumed the position of Professor at Institute for Liberal Arts, Tokyo Institute of Technology.

Hiroichi Yanase | Tokyo Tech STAR Search

The Special Topics component of the Tokyo Tech Website shines a spotlight on recent developments in research and education, achievements of its community members, and special events and news from the Institute.

Past features can be viewed in the Special Topics Gallery.

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.