The first college woman in Japan was a rikejo

There have been many strong and radiant women in Japan over the years who painstakingly paved the way for women's accomplishments in a patriarchal society. There were Raicho Hiratsuka and Fusae Ichikawa, women's emancipation leaders who founded the New Women's Association and contributed to obtaining women's suffrage and political rights in Japan in the periods before and after WWII. There was Shoen Uemura, the first woman to be presented with the Order of Culture, who made her name with her bijin-ga (beautiful women paintings) in an unsympathetic world. Then there was Yoshiko Mibuchi, one of the first female lawyers in Japan, who became the first woman judge in the Nagoya District Court in 1952 and the first woman chief justice of the Niigata Family Court in 1972. This article, however, focuses on rikejo or women in the sciences who were pioneers in this male-dominated field and who experienced successes despite seemingly overwhelming obstacles.

Approximately 100 years ago, in 1913, three young women passed the entrance exam to Tohoku Imperial University. This event is regarded as having given birth to the first college women at a Japanese University. It also triggered massive protests across Japan, was viewed as abhorrent by some, and aroused controversy over who should be considered eligible to sit for college entrance examinations.

The first Tokyo Tech female student was virtually a single mother who taught during World War II

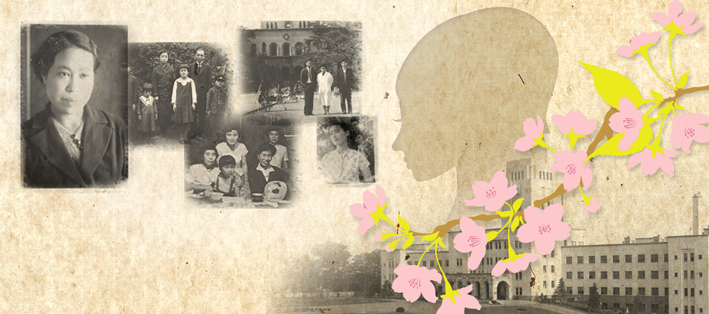

Sada Orihara was Tokyo Tech's first female student. After graduating from the Maebashi Girls' Senior High School, she went on to study the sciences at the Tokyo Women's Higher Normal School (currently Ochanomizu University) in 1926, where she became assistant professor after her graduation. With the encouragement of those around her, Orihara decided to enter Tokyo Tech's Department of Dye Chemistry as a sponsored scholarship student in 1931. Among the nearly 150 students admitted that year, she was the only woman. Orihara was one of 13 students to enroll in the Department of Dye Chemistry, together with Kiyoshi Takiura, her future husband. After earning her degree at Tokyo Tech, she returned to teaching at the Tokyo Women's Higher Normal School.

Orihara married in 1939 and gave birth to a son shortly thereafter. The Pacific War (1941- 1945) broke out when her son was two years old. In 1943 her husband was transferred to the Kansai region. Orihara remained in Tokyo and brought her son to her workplace each day, letting him play under her desk while she taught. In 1944 when the air raids on Tokyo intensified, she was forced to evacuate with her son to her family home in Maebashi. This was the beginning of an extremely difficult period for her as she had to take the first train in the morning to commute to Tokyo for work. Even though her efforts were rewarded with the position of professor at the Tokyo Women's Higher Normal School, she stepped down from her professional career upon evaluating the difficulties of single parenting while trying to work in the chaos of postwar Japan. She joined her husband in 1946 in Kobe and began domestic life. She gave birth to a second son in 1948 and devoted herself to her family as a mother and wife. Needless to say she faithfully supported her husband and contributed to his achievements in this way. One of Takiura's accomplishments, thanks to her support, was the founding of Osaka University's Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences. Orihara died young at the age of 52, possibly due to pushing herself too hard for too many years. Her life bears witness to the immense challenges of maintaining and furthering a career as a woman and the hardships of being a single parent complicated by war.

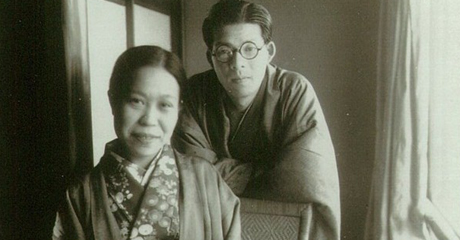

Sada Orihara

Photo courtesy of Ochanomizu University

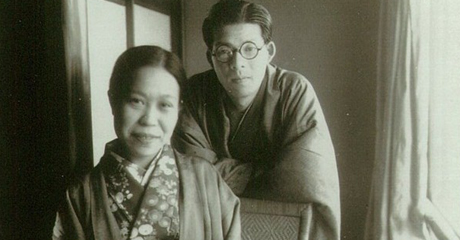

Sada Orihara and her husband, Kiyoshi Takiura

Tokyo Tech's pioneering rikejo in the postwar period

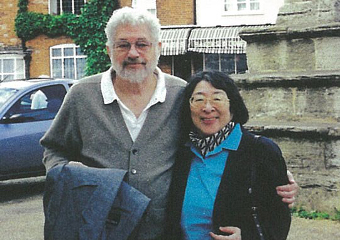

Michiko Togo, another pioneering college woman, entered Tokyo Tech after passing the entrance examination in 1947, two years after the war ended. Togo came from two generations of scientists. Her maternal grandfather, Kunihiko Iwadare, founder of NEC Corporation, was also known as the one who impressed the famed Thomas Edison. Her father was a graduate of Tokyo Tech. She desperately wanted to become an engineer in order to be able to contribute to Japan's postwar recovery. Togo's determination enabled her to pass the exam despite the fact that only about 21 percent of aspiring candidates succeeded in passing. However, once on campus, she experienced a considerable degree of culture shock. Her greatest problem was the absence of a women's bathroom. Togo used a gender-neutral bathroom when there was no man present. But when a man entered, she remained in her stall out of embarrassment till he left the bathroom. Finally, she consulted with her academic supervisor and managed to obtain a paper sign saying “women only” to put on one bathroom door. Despite these and similar embarrassments, her presence was so strong that other students quietly respected her as the “only girl.” Togo studied in the Department of Electrical Engineering with classmates who had experienced battle. After graduating from Tokyo Tech, she told herself that it was imperative to take a look at the country that defeated Japan, so she went to study in the United States for two years. During her stay she also attended Bryn Mawr College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where Umeko Tsuda, founder of Tsuda College, was once enrolled. Here Togo had a fateful encounter with Shigeru Yoshioka who was studying at seminary. Once back in Japan, she married him and supported him in his calling as a pastor in missionary activities in Sendai and Kobe.

Now in their mid-80s, Shigeru and Michiko (Togo) Yoshioka still attend the seminar series Reading the Old Testament, hosted by the Tokyo Tech Alumni Association, when their health permits it.

Togo has spent a lot of time gathering and organizing many historical documents related to Tokyo Tech and electrical engineering education. She is often referred to as an electrical technician who became a technician of memoirs and as such, she is also a pioneer of lifelong learning.

Michiko Togo and classmates

The women in science who blazed new trails

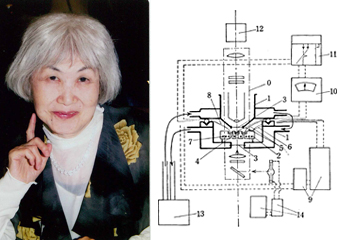

Kayako Tanaka

The achievements of women who studied at Tokyo Tech gained a new dimension after 1945. Kayako Tanaka graduated from Tokyo Tech's Department of Applied Physics in 1952. She married Ken-ichi Hirano who joined the department in the same year. In 1957 both of them went to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where she became absorbed in her experiments. They were blessed with a child. However, in 1962 when Tanaka (Mrs. Hirano) was finishing up her doctorate, she passed away from cancer at the young age of 37. The local paper, the Boston Traveler, praised her achievements and announced her posthumous degree by publishing an article on June 8, 1962 about her with the title “Hirano's Gone But Honors Live.” This article appeared the following month in Japan in the Asahi Shimbun.

Kimiko Sato and her academic supervisor at Tokyo Tech,

Professor Seita Sakui

Another pioneering woman in science, one who laid the ground for women to obtain doctoral degrees, is Kimiko Sato, nicknamed Hamu-chan. She became the first woman doctor of engineering. She worked as a technical specialist and an academic assistant at Tokyo Tech and obtained her doctorate in engineering at the age of 38, in 1962. Then in 1968, Sato moved to the University of Electro-Communications where she contributed to educational research in the fields of metallic materials and machine engineering.

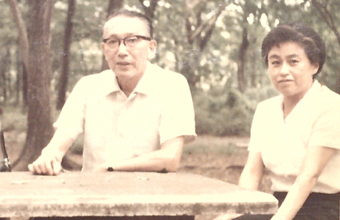

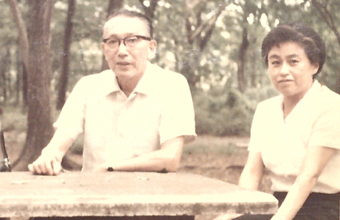

Setsuko Tanaka and her husband, John Blackmore

Setsuko Tanaka, Kazuko Kunihisa, and Aiko Nabeya were the last female students to enroll in 1950 under the old education system. Tanaka studied science at the Women's Higher Normal School, then went on to study and graduate from Tokyo Tech. In 1965 she transferred to Aoyama Gakuin University's College of Science and Engineering, which had been established in that same year thanks to the immense support of a Tokyo Tech professor, and taught physics there to liberal arts students. Largely through trial and error she is said to have explored the commonalities between the arts and sciences. Kunihisa graduated from the Tokyo College of Science (currently the Tokyo University of Science) in 1950, then entered Tokyo Tech to study physical chemistry. She then worked at the Tokyo Industrial Research Institute of the Agency of Industrial Science and Technology, and dedicated her life to research. She developed a compact thermal analyzer which made thermal analyses possible while observing samples under a microscope. This equipment contributed to the significant advancement in research on liquid crystal. Nabeya, who graduated from the Department of Chemistry at Tokyo Tech in 1953, continued her research in the field of organic chemistry under Yoshio Iwakura, professor in the Chemical Resources Laboratory and world expert on Synthetic Organic Chemistry.

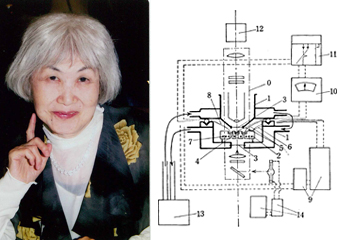

Kazuko Kunihisa and the apparatus

for thermal analytic microscopy she developed

Aiko Nabeya (back row, left)

The position of women gradually rose after WWII with the promotion of gender equality. However, rikejos had to make extraordinary efforts to balance their family, work and research lives, which required a great deal of time and effort. Kunihisa kept using her maiden name for her research papers even after she got married, but the question of using a maiden name when authoring a paper is still troubling for women today. Nonetheless, each effort made by these pioneering women has furthered the position of Japanese women in the sciences today.

This article is an excerpt from a Tokyo Tech Museum and Archives flyer which was first published in October 2013.

The Special Topics component of the Tokyo Tech Website shines a spotlight on recent developments in research and education, achievements of its community members, and special events and news from the Institute.

Past features can be viewed in the Special Topics Gallery.

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.