The effects of climate change associated with global warming are diverse, and one of the most severe is flooding. In fact, in fall 2019, two super typhoons (Faxai and Hagibis) hit Japan in succession, causing devastation across the country. We asked two emerging researchers in flood mitigation about new approaches to reducing damage from floods.

Assistant Professor Rie Seto of the School of Environment and Society, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, conducts cloud research for improving accuracy of precipitation forecasts. Assistant Professor Rei Itsukushima of the School's Department of Transdisciplinary Science and Engineering studies flood control measures based on awareness of historical flood control systems and microtopography*.

*Microtopography: terrain variations on the scale of 1/50000 to 1/25000, features smaller than what topological maps can clearly show

(Interview held on March 4, 2020)

Current challenges posed by major flooding

Rie Seto

In recent years, there has been a surge in major floods in Japan and elsewhere. What current challenges do major floods pose?

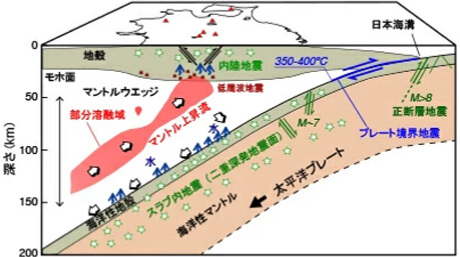

Seto: Infrastructural measures have been taken to reduce flood damage, such as building dams to store rainwater and levees to prevent flooding; and they have been beneficial. But in recent years, typhoons and heavy rains have become more frequent, and existing dams and levees are no longer able to prevent flood damage. Furthermore, constructing new dams and levees can be enormously expensive and time-consuming, and in any case, no suitable locations in the city are left to build them. So it's not a practical solution.

On the other hand, I do not believe that existing dams are being fully utilized. Especially for multipurpose dams, used as both a water source and for flood control, it would be very effective if the water volume could be adjusted in advance, for example by discharging accumulated water before a typhoon or heavy rain. This could reduce the likelihood of flooding in downstream rivers. When Typhoon Hagibis made landfall in October 2019, the Yamba Dam under construction on a Tone River tributary was in the experimental storage stage, so it was almost empty. The flooding of Tone River was prevented partly thanks to accumulation of rainwater there, which revealed the possibility of more effective use of existing dams.

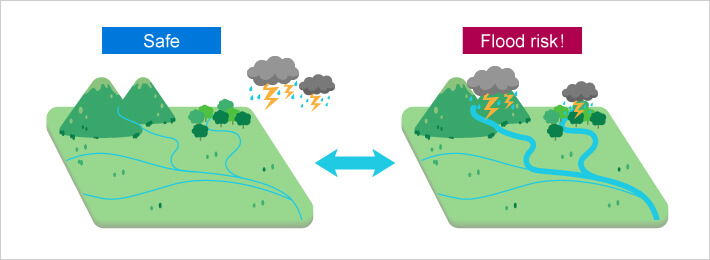

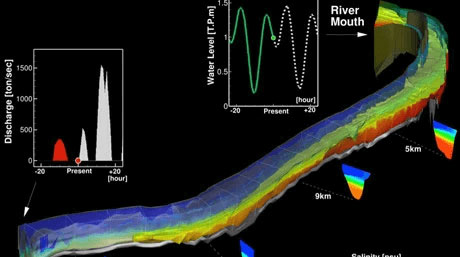

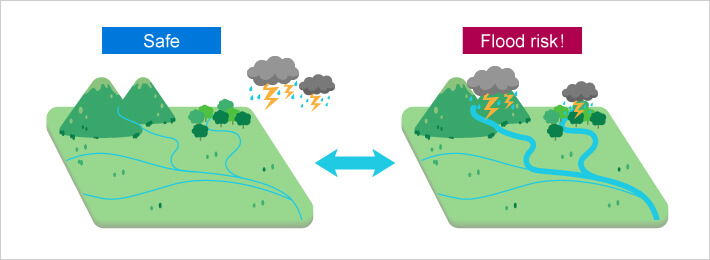

The biggest reason that flood control in dams has not been fully utilized lies in the inaccuracy of typhoon and heavy rain forecasts. In order to release water from dams in advance, it is necessary to accurately predict when, where, and how much rainfall will occur. If water is released in advance, but rainfall is less than expected, it will have a significant effect on water use and power generation. In particular, it is important to predict the location of the rainfall. The amount of water stored in the dam varies greatly, depending on whether rain falls within or outside of the river basin. Despite that, the main focus has been on predicting amount of rainfall, without much progress in pinpointing predicted location of rainfall. Therefore, I am focusing on ways to improve the accuracy of rainfall location prediction.

Flood risk greatly depends on whether rain falls outside (left) or over (right) the river basin.

Rie Seto's research focuses on ways to improve accuracy of rainfall location prediction.

Itsukushima: As Seto-sensei mentioned, Japan has been preparing for flood damage since the Meiji era, mainly by constructing dams and continuous levees. As a result, the frequency of floods and the extent of inundations during flooding have steadily decreased compared to the past. Lowlands that are more likely to be flooded when rivers overflow are called floodplains. Thanks to dams and levees, we are now able to live in places like floodplains, which were previously uninhabitable due to frequent floods. But that's not entirely positive. This is because the risk is larger for unexpectedly major flooding. In addition, as the number of people affected by floods decreases, the sense of impending crisis due to floods also diminishes. With fewer people in a vicinity being affected by flooding, experience with flooding does not get passed down.

Rei Itsukushima

In recent years, major floods have been frequent, with incidents such as the 2015 heavy rains in Kanto and Tohoku, the 2017 heavy rains in northern Kyushu, and typhoon Hagibis in 2019. Existing dams and levees have become unable to cope. Nevertheless, even if dams and levees are built to handle major floods with an occurrence probability of once every 150 or 200 years, even more floods than that will occur in the future. As Seto-sensei mentioned, building new dams and levees alone is not enough.

The aim of my research is to reduce damage on floodplains when they become inundated by rivers. In particular, I focus on flood control measures based on an awareness of historical flood control systems and microtopography. In the days when technology for building levees or dams at major rivers did not exist, people lived where floods were less harmful. They devised ways to mitigate flood damage by controlling flow and momentum. These structures and systems have disappeared as modern control measures have reduced flood damage and advanced land use. My research involves reconsidering historical flood control systems and combining them with modern control measures from the Meiji era onward to reduce major flood damage in floodplains. I believe that these measures will not only reduce flood damage, but also restore and preserve the natural environment.

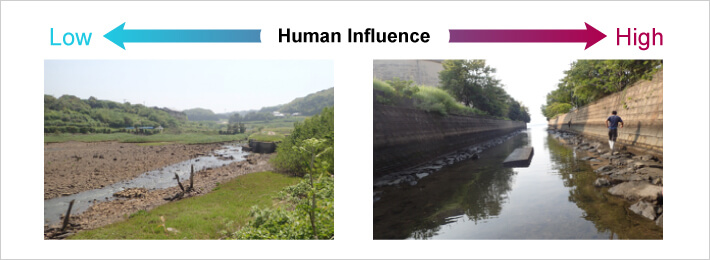

A river that has seen little human influence (left) and one heavily influenced (right).

Rei Itsukushima is studying ways to mitigate flood damage through environmental restoration and preservation.

Cloud data is a plus for weather forecasting

Prof. Seto, tell us more about your research.

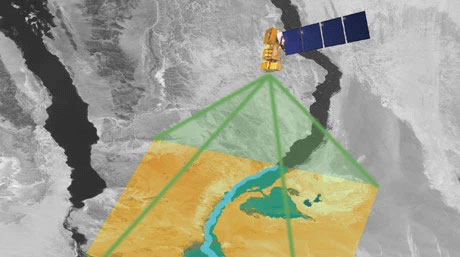

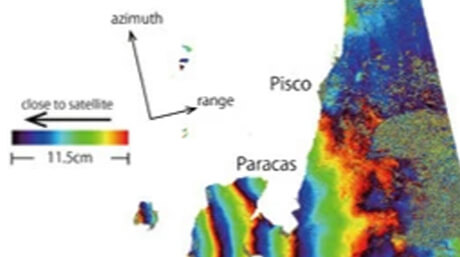

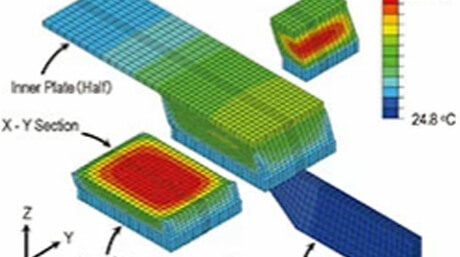

Seto: To improve accuracy of rainfall location prediction, I observe cloud water content using satellites, thereby improving the accuracy of computer simulations. Cloud water content is the amount of water contained in clouds.

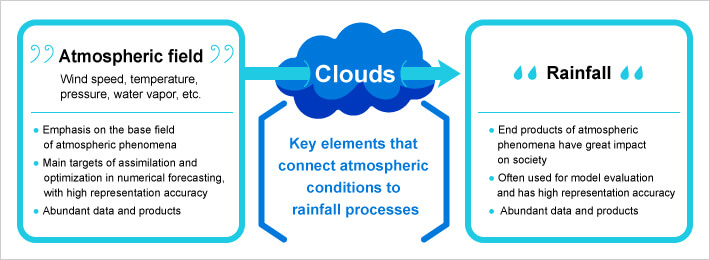

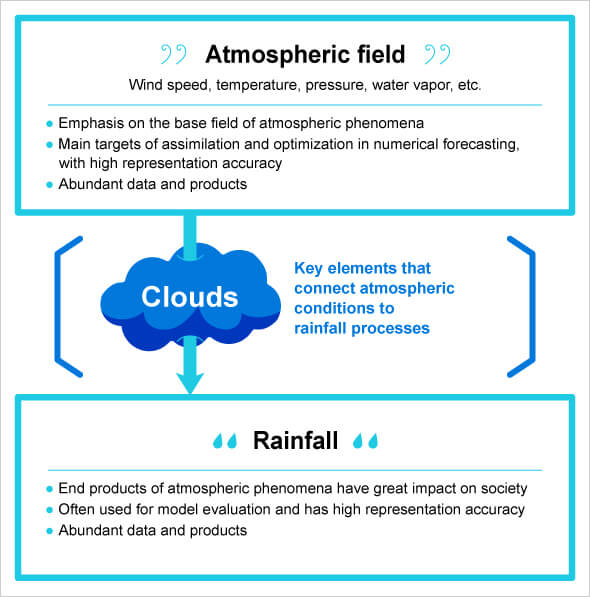

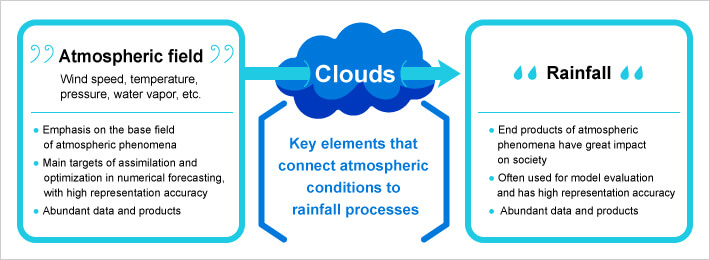

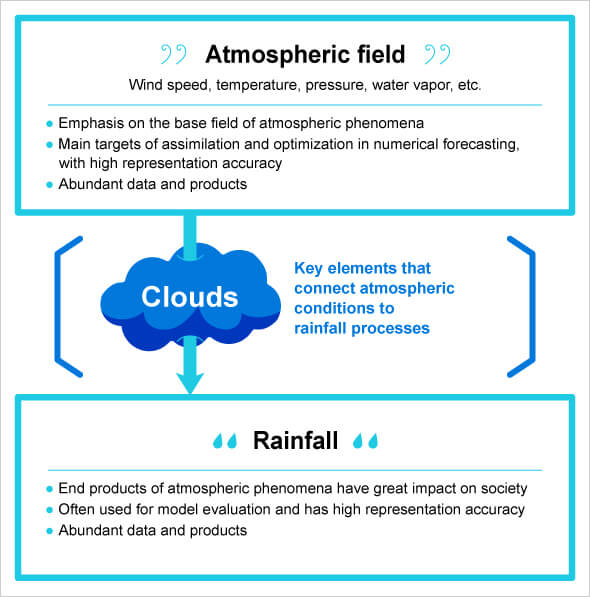

Part of the critical data on which weather forecasts are based is atmospheric field. Atmospheric field includes wind speed, temperature, and pressure. Atmospheric motion occurs in response to instability of the atmospheric conditions, causing cloud formation and rain. Numerical models called "weather models" are used for weather forecasts. Conventional weather models focus on replicating atmospheric conditions and rainfall, without focusing on the clouds between them. That's why so little is known about how accurately the models represent the water content of the clouds. Also, the means to measure them accurately have been limited.

Conventional weather models have focused on atmospheric conditions and rainfall.

Rie Seto focuses on accurately determining the water content of clouds, which links the former two concepts.

Why is it difficult to measure cloud water volume?

Seto: If you look up at the sky, you can see that clouds are very unevenly distributed. To understand the distribution of the cloud water volume, we need to measure at not only one place or one time, but as widely and frequently as possible. Therefore, satellite-based methods are suited to monitoring cloud water content. The most widely used method is satellite-based passive microwave observation, where microwaves emitted from clouds and picked up by satellites can be used to estimate moisture content. However, it is not easy to estimate this with satellites, since clouds have cloud droplets, raindrops, ice, and snow of various sizes all mixed in and distributed in a complex manner. In addition, there are significant barriers to observing cloud water volume, especially over land. Microwaves are also emitted from the ground surface below the clouds. Sea is somewhat uniform, but land has forests and cities as well as rivers. The temperature and moisture content of the ground surface are not uniform, so microwave radiation from the land disturbs signals from clouds. In order to monitor the cloud water content over land with high accuracy, we need a good understanding of the conditions of the land. This requires some skill and is not easy. Measuring land and clouds at the same time is a particular focus of my research.

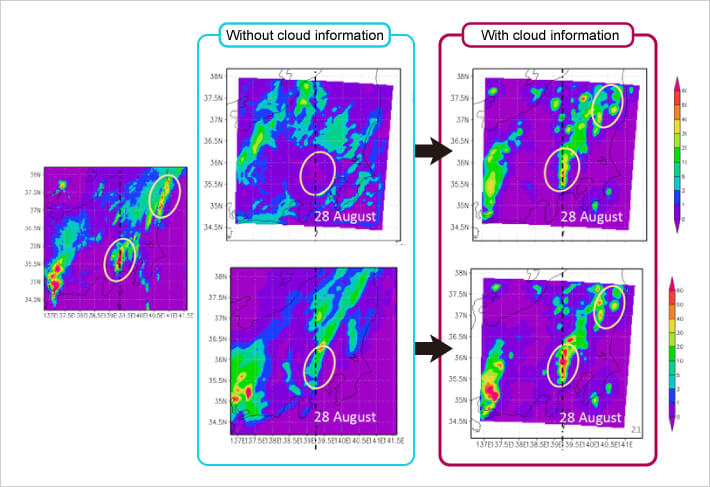

For short-term weather forecasts of several hours to several days, the accuracy of forecasts varies greatly depending on the initial values given to the weather model. My approach is to try to predict rainfall location accurately by inputting satellite observation data for cloud water content into the initial values. At present, our predicted rainfall locations closely match actual locations. With accurate rainfall location prediction, we are aiming to extend the lead time of forecasts and improve overall accuracy.

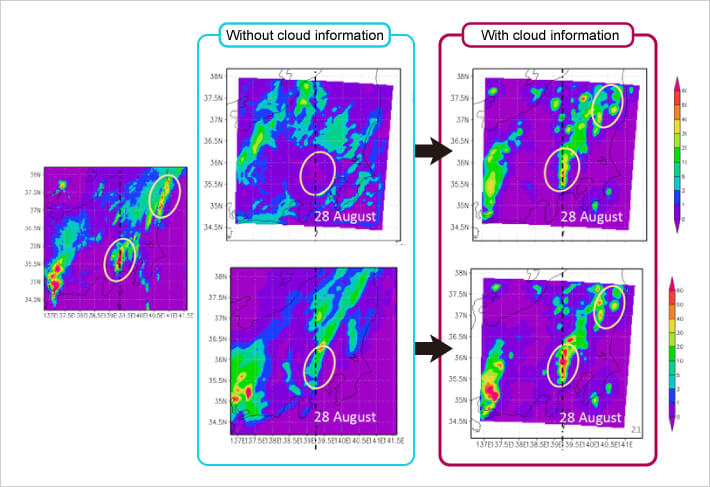

Forecasts using observations of cloud water volume. Lower left: actual rainfall conditions. Top center: without cloud information. Top right: with cloud information, Seto’s method correctly forecasted unpredicted rainfall. Lower center: conventional model predicted heavy rain at the wrong location. Lower right: Seto’s method predicted heavy rain at the correct location.

Measures to prevent floods from causing flood damage

Prof. Itsukushima, tell us more about your research.

Itsukushima: To begin with, the terms flooding (kouzui) and flood damage (suigai) are often confused. Flooding is a natural phenomenon in which water overflows from rivers due to heavy rain, and the damage caused by flooding is flood damage. The important point is that floods do not result in flood damage.

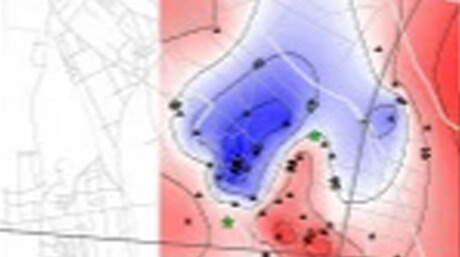

Modern flood control measures since the Meiji era have reduced the frequency of floodplain flooding, drastically changing land use. The flood control systems built on floodplains are disappearing. So in some areas, the damage potential from major flood damage is even increasing. I use historical topographic maps, aerial photographs, and literature to investigate the disappearance of flood control structures and land-use changes.

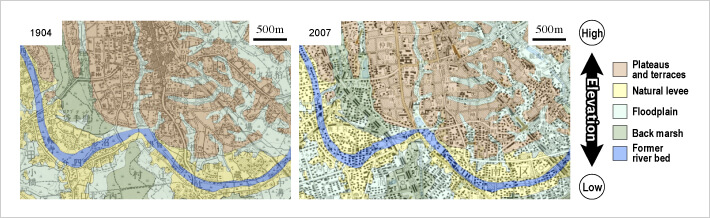

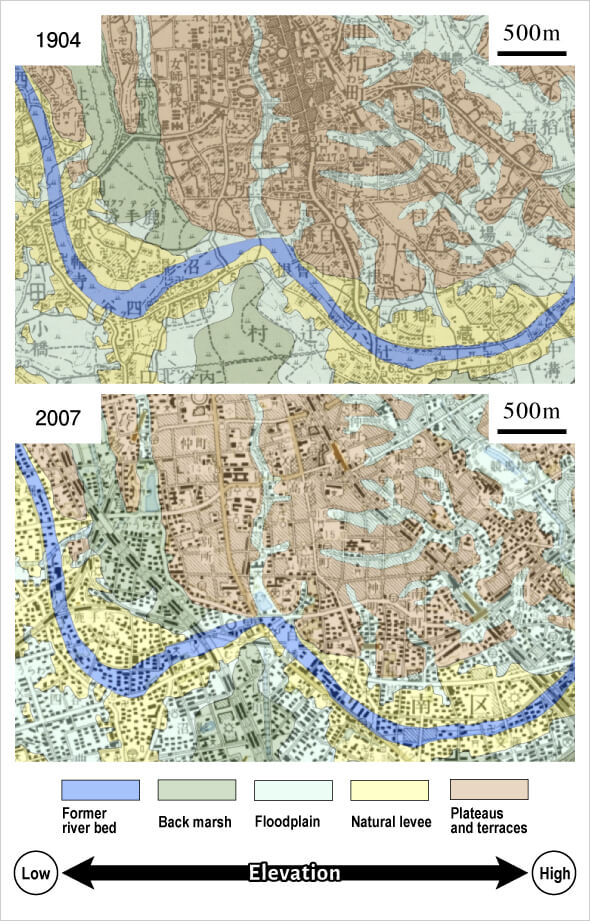

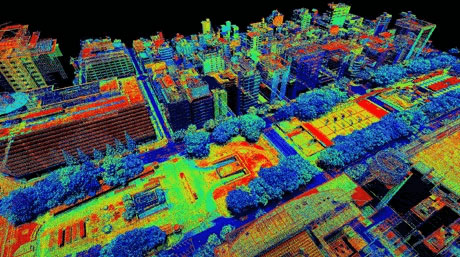

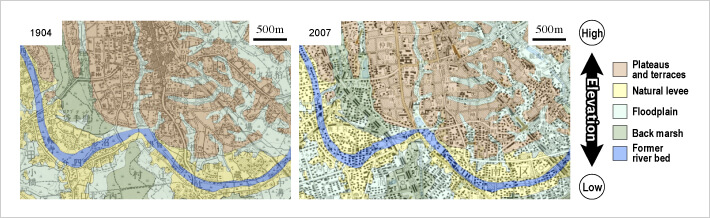

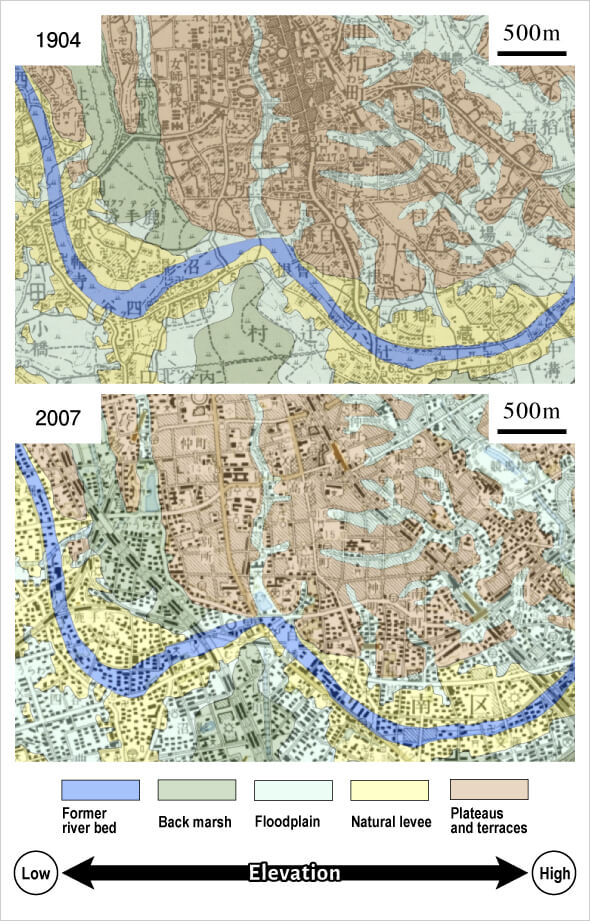

"Flood control topographic classification map" showing the properties and conditions (such as ground height and soil quality) of the terrain distributed in the plain. It reveals the elevation of the land and the conditions of past floods. Orange indicates a high-altitude plateau, yellow indicates a slightly higher natural levee created by the rise of sediment carried by rivers onto riverbanks, light blue indicates a floodplain submerged by flooding, green indicates a back marsh where puddles are prone to forming, and blue indicates a former river bed where a river used to flow. Comparison of maps showing land use at a station between 1904 and 2007. This reveals that in 1904, the urban area was concentrated on plateaus, and floodplains and back marshes where floods were likely to occur were generally uninhabited wastelands and rice fields. But in 2007, all terrains including floodplains and back marshes showed development underway. (Created based on the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan's flood control topographic classification map)

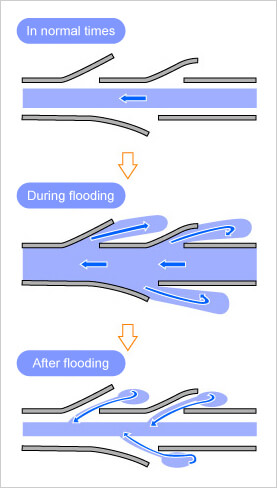

Open levee (kasumitei), a traditional flood control system.

(Source: National Institute of Land and Infrastructure Management)

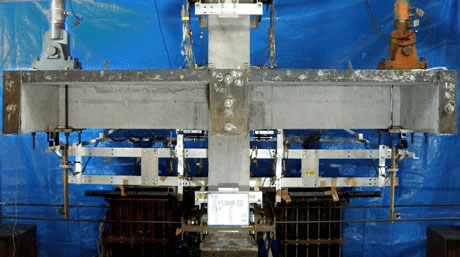

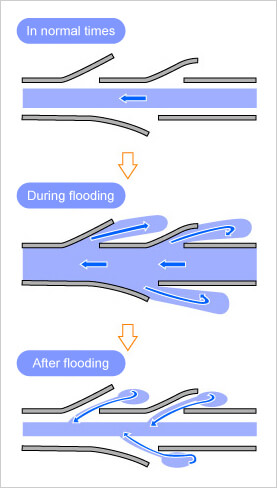

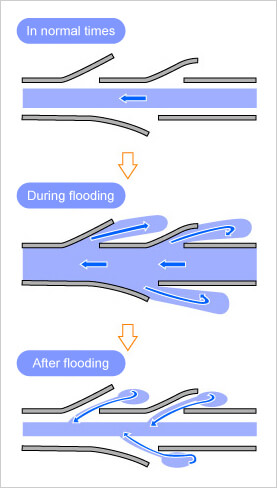

At present, most of the levees are continuous, mainly in urban areas. But old levees were discontinuous levees to provide local defenses, with intentional openings. In addition, many discontinuous levees for controlling floods have been set up, both along rivers and on floodplains. A typical one is called an open levee (kasumitei). The right is upstream and the left is downstream. When the water level of the river rises due to flooding, water flows backward from the opening of the open levee. Furthermore, when the water level falls, the overflowing water returns from the opening, eliminating inundation from flooding. This reduces the amount of water going downstream, thus reducing flood damage.

Open levee (kasumitei), a traditional flood control system.

(Source: National Institute of Land and Infrastructure Management)

To prevent the water from overflowing at all, the river width must be widened, and in narrow areas such as mountainous areas, cultivated land is narrowed accordingly. Open levees, on the other hand, not only protect the downstream from flood damage, but also cope with flooding without narrowing the cultivated land. Most levees at present are continuous levees, but open levees remain at the Kuji River in Ibaraki Prefecture, the area I am studying.

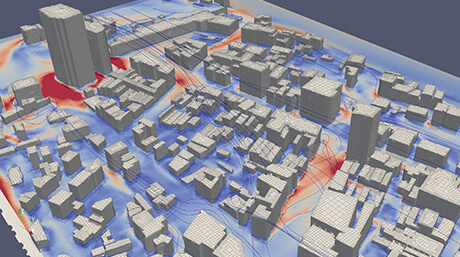

In addition, in order to quantify how discontinuous levees such as open levees function in the event of major flood damage, inundations in the present with continuous levees and in the past with many discontinuous levees have been reproduced by computer simulation. This has revealed that with continuous levees, the flood area is small, but once flooding occurs, there is no place for the flood water to return to the river, creating places where flood water can easily collect locally. In the past however, when discontinuous levees were set up, the flood area was large, but the inundation spots were dispersed, and it was confirmed that the flood water level and flow velocity were low.

The old flood control structures are filled with the wisdom of our ancestors. The past is truly a guide to the present.

Itsukushima: Indeed. Based on the results of these studies, it would be possible to reduce major flood damage on floodplains by combining historical flood control systems with the river infrastructure currently in place, such as levees and dams.

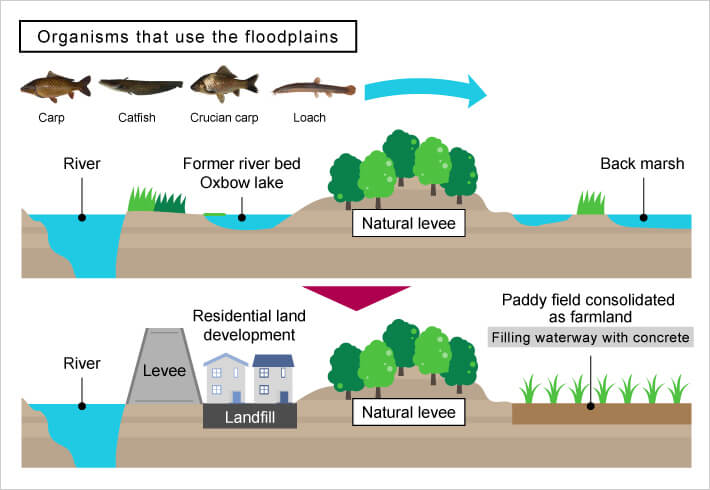

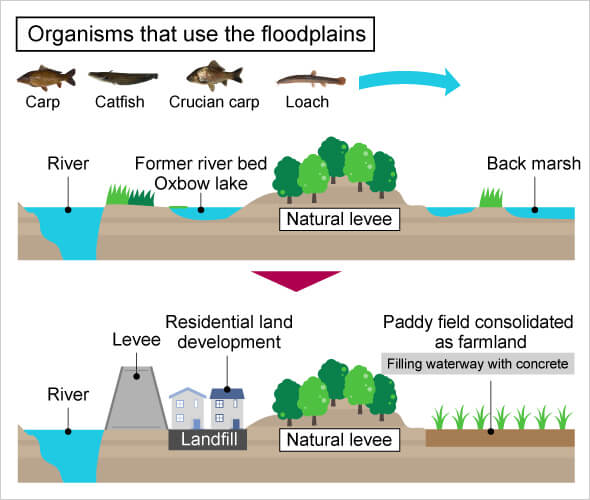

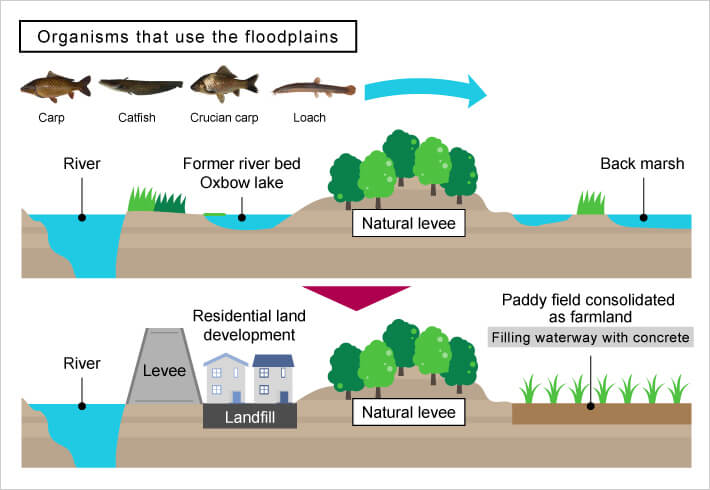

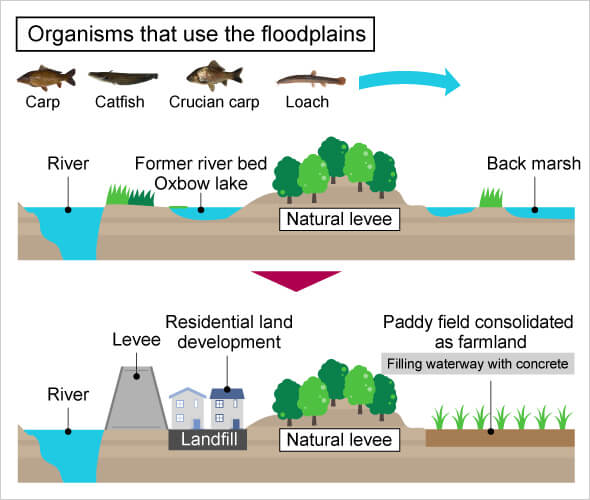

In addition, I think that flood control measures that tolerate flooding can solve both environmental and flood challenges. In Japan, there are many organisms that have adapted to the flooding environment. Many of them are now in danger of extinction as the frequency of floodplain flooding has decreased. Catfish and crucian carp entered the back marshes and old river beds used as paddy fields from rivers during floods, and laid eggs there. If, as is the case today, the floodplains and rivers are completely separated by continuous levees, the habitats of these rivers will decrease, and the creatures will become fewer. Therefore, in terms of maintaining nature and ecosystems, it makes sense to utilize the old river beds and back marshes as a storage space for flood waters, and to take flood control measures that tolerate inundation.

The floodplain ecosystem disappeared because of the disruption of continuity between floodplain and river due to river modifications, farmland consolidation, and residential development.

Opportunity to start the research

What first motivated you to pursue this research?

Seto: From a young age, I loved looking up at the sky and clouds, and couldn't resist looking things up when I had questions about natural phenomena. So I had a vague idea that I wanted to be a researcher in natural phenomena. At one point I was interested in astronomy and physics, but I also had a strong desire to help society in addressing environmental issues. I chose to go into the field of social infrastructure at university, and my current research satisfies my desire to get involved with both nature and society.

Itsukushima: I was born in a suburb of Funabashi City, Chiba Prefecture, where a relatively large amount of nature remained. When I was a child, wetlands and rivers called "yachi" were my playground, but while I was in elementary school, these places were gradually lost due to railway construction and residential development. As I grew up, it made me feel lonely how the natural world where I had played as a child was disappearing. I became interested in environmental issues and the field concerned with rivers, which were my playground. At university I learned about river environment conservation. After completing graduate school, I joined the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism and worked on tasks related to flood damage. That has led to my current research on flood control measures on floodplains. Disaster and environment related issues often cannot be solved within rivers, and the river basin must be targeted. I became a researcher because I wanted to consider river issues from a broader perspective.

Thinking about what we can do

What advice would you give others on measures to take in the event of possible flood damage?

Seto: First of all, it is important to think about all possible dangers to yourself. This can only be done in normal times, so we should get started right away. Specifically, it is a good idea to look at a hazard map to see how much current risk there is for flooding where you live. I live near the Tama River, so during Typhoon Hagibis last year, I checked a hazard map to see if there was a possibility that my place would be flooded. There wasn't, so I didn't need to panic. If you learn from a hazard map that you live in a high-risk area, it is important to evacuate as soon as possible. But as for landslides, the hazardous areas on hazard maps are extensive, and you do not know when or where one will occur. So you will have to make difficult decisions. But any way you look at it, the first step in preparing for disasters is to find out what kind of area you live in. Another important thing is to track the forecasts and warning information from the Meteorological Agency in a timely manner. The accuracy of forecasts has been significantly improved in recent years, although the accuracy at small scales such as the location of rainfall is still lacking, as mentioned earlier. Rather than relying on your own experience to determine whether you're in the clear, strictly complying with forecasted alerts and warnings can help you to protect yourself.

Itsukushima: I also think it is very important to be interested in the area where you live above all. For example, place names supposedly reflect the history of past disasters, so it may be helpful to look into the history of the area where you live to help you develop countermeasures.

I live near the Gotanda River, which pours into the Tama River. The Gotanda River is a typical urban river covered with concrete. However, the other day I was overjoyed to find a kingfisher at the river. I would like people to be at least a little interested in the natural environment of the rivers where they live, for example by watching birds or fish.

Rie Seto

Assistant Professor, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, School of Environment and Society

- 2017: Started current position

- 2016: Project Researcher, Institute of Engineering Innovation, School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo

- 2015: Project Researcher, the University of Tokyo Earth Observation Data Integration & Fusion Research Initiative

- 2015: Doctor of Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo

- 2012: Recipient of the JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists PD (DC1)

- 2012: Master of Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo

- 2010: Bachelor of Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering, School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo

Conducts research in hydrometeorology and water engineering with the aim of contributing to climate change solutions and flood damage countermeasures. Applies artificial satellites and numerical models for measurement, comprehension, and prediction of cloud rainfall phenomena.

Rei Itsukushima

Assistant Professor, Department of Transdisciplinary Science and Engineering, School of Environment and Society

- 2019: Started current position

- 2014: Assistant Professor, Kyushu University

- 2013: Doctor of Engineering.

- 2009: Worked on the design and execution of flood control operations, promotion of overseas projects related to disaster prevention, and formulation of river plans at the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

- 2009: Master of Engineering, Department of Civil and Structural Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyushu University

- 2007: Bachelor of Engineering, Department of Earth Resources, Marine and Civil Engineering, School of Engineering, Kyushu University

Focused on river basins from headwater to coastal areas, conducts research on flood damage, river topography, and river ecosystems. Works to contribute to development that achieves harmony between the natural environment and human society.

More Tokyo Tech research on natural disaster countermeasures

Extreme weather (torrential rain, floods, high winds, storm surges)

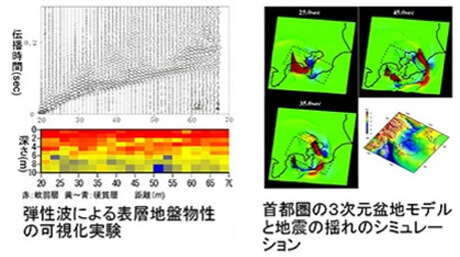

Earthquakes and volcanic activity (ground, tsunamis, eruptions)

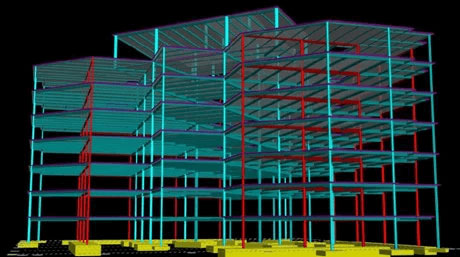

Disaster-resistant construction and infrastructure

NEXT generation is a new series about emerging researchers, working at the forefront of science and technology as they envision the impact their discoveries will have on society's future.

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.