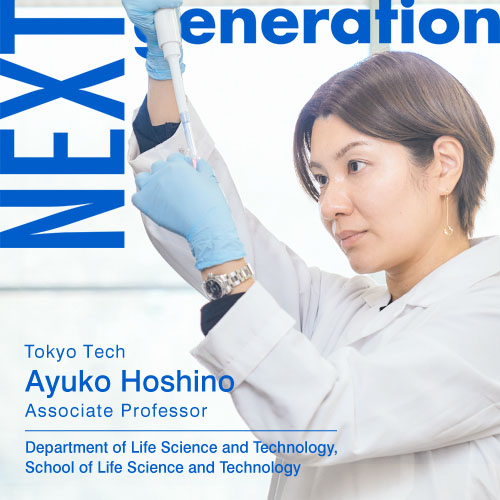

"Exosomes" are tiny particles released by all cells. Ayuko Hoshino, an associate professor at the School of Life Science and Technology, was the first to discover that exosomes are involved in determining which organs certain cancers metastasize to. The research is gaining much attention, with the hope that it will lead to revolutionary diagnostic methods and treatments for cancer and other diseases.

After spending eight and a half years training at Weill Cornell Medicine, Hoshino joined the School of Life Science and Technology as an associate professor in March 2020. Here we introduce her extraordinary research journey.

Survival rate drops once cancer spreads to other organs

First, tell us about your research.

I am researching how cancer metastasizes. There are many types of cancer, including breast, lung, and pancreatic cancers. Cancers that develop in each of these organs are called primary cancers. As the primary cancer grows, it can enter blood and lymph vessels, and metastasize to other organs, becoming metastatic cancer. For example, in breast cancer, while it is in the primary cancer stage, the survival rate after 5 years is 90% or higher. But once it metastasizes, survival rate drops to around 30%. Once a cancer metastasizes, it becomes much more difficult to treat.

It's actually not easy for cancer cells to metastasize. Blood flows through vessels at a tremendous speed. And even if cancer cells get close to the organ to which they metastasize, it is not easy for them to remain there, pass through the narrow gaps between cells, and then spread to other organs. Moreover, it has been known for more than 130 years that the organs to which a cancer metastasizes are strangely limited depending on the type of cancer. For example, breast cancer tends to metastasize to the brain, lungs, liver, and bones; while metastasis by osteosarcoma (a type of bone cancer) is often limited to the lungs; and pancreatic cancer tends to metastasize to the liver. However, the mechanism behind this tendency of cancer to metastasize to certain sites remained a mystery for many years.

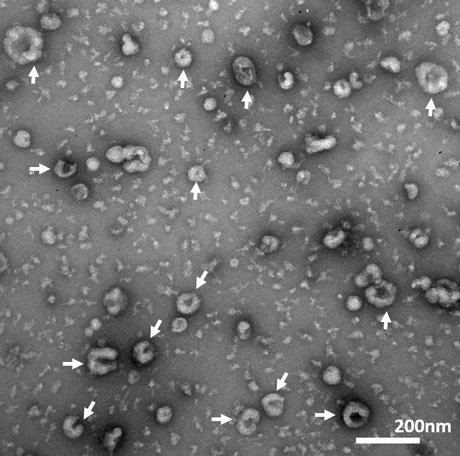

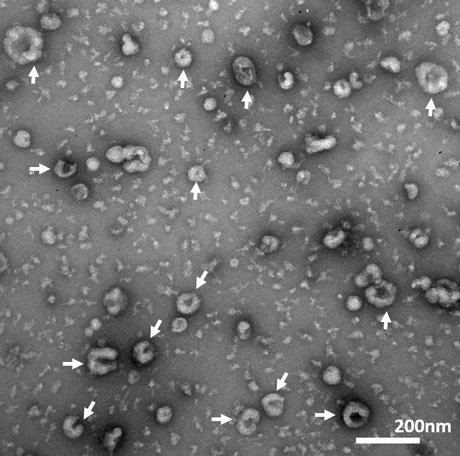

I found that exosomes are deeply involved in cancer metastasis, and now I'm studying their mechanism. Exosomes are tiny particles about 30 to 150 nanometers (billionths of a meter) in diameter that are released by all cells. They are only about the size of a virus. Exosomes have traditionally been considered as "garbage bags" that remove unwanted substances from inside cells. But in recent years, it's been found that exosomes released from one cell can be taken up by other cells, and that exosomes act as a communication tool between cells.

Electron micrograph of exosomes — only about the size of a virus, these tiny particles are released by all cells

Exosomes use postal codes?!

How are exosomes involved in cancer metastasis?

Cancer cells and the organs to which they metastasize have a relationship like seed and soil. If you try to plant corn in different parts of the world, it will not grow in all soils. It's believed that exosomes play a role in cultivating an organ (the "soil") such that cancer cells (the "seed") can grow in it. I am working to understand this mechanism.

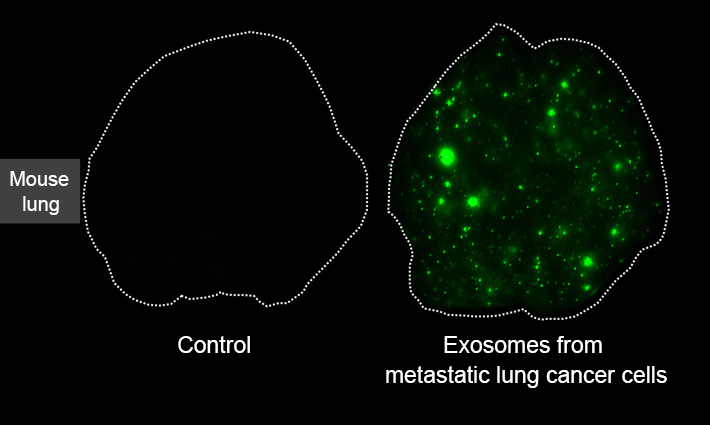

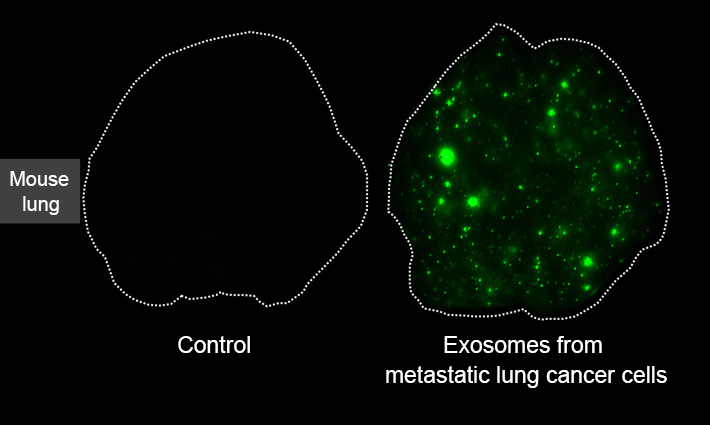

Therefore, we injected exosomes released by various types of cancer cells into the blood circulation of mice. We confirmed that exosomes released by cancer cells that metastasize to the lungs went to the lungs, and exosomes released by cancer cells that metastasize to the liver went to the liver.

We also performed a proteomics analysis to verify the protein cargo differences between exosomes that localizes to different organs. In 2015, we discovered that each exosome produced by cancer cells has something like a postal code in regards to metastasis.

The "postal code" was a protein called integrin. Integrins are proteins involved in cell-to-cell adhesion. Regardless of the type of cancer, it became clear that exosomes released by cancer cells that metastasize to the lungs have an integrin named α6β4, and the exosomes released by cancer cells that metastasize to the liver have an integrin named αvβ5. Conversely, when these integrins were removed from the exosomes, the cancers did not metastasize to those organs. It turned out that there is a strong relationship between the organ to which these cancers metastasize and the expression pattern of the integrins. We published these findings in Nature in 2015.

Exosomes reach the future site of metastasis before cancer cells and change cells at the site, making it easier for cancer cells to metastasize

My ultimate goal is to help create new diagnostic and therapeutic methods based on exosomes

What are your future research goals?

The interesting thing about exosomes is that they are released from every cell and are involved in the various cellular changes that occur in the body.

Even if two diseases that are related to the same organ seem completely different in regard to etiology, such as cancer cells that metastasize to the brain and autism spectrum disorder, we can infer that they may share a common mechanism. For example, we are realizing that both exosomes easily reach the brain and influence the brain environments. Therefore, since early on, I've been interested in doing research on exosomes in different types of diseases which focus on the same organs.

When it comes to other diseases, analysis of exosomes targeting the same organ will eventually reveal how the exosomes are involved in disease progression. If a common mechanism can be identified, it could be revolutionary for diagnostic, treatment, and therapeutic methods of diseases. By collecting blood and analyzing the exosomes that are present, early detection and treatment of various diseases, including cancer, would be possible. For example, the likelihood of metastasis could be reduced before a cancer spreads. My ultimate goal as a researcher is to help create new diagnostic and therapeutic methods based on exosomes.

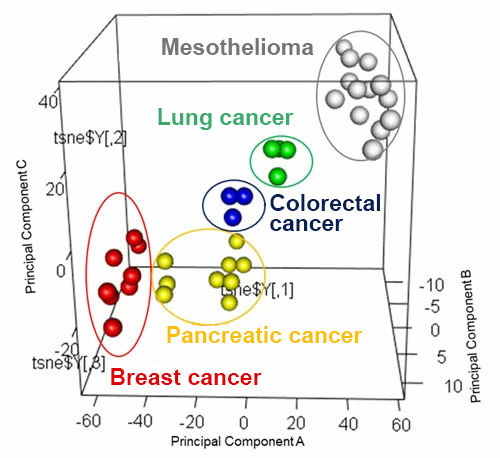

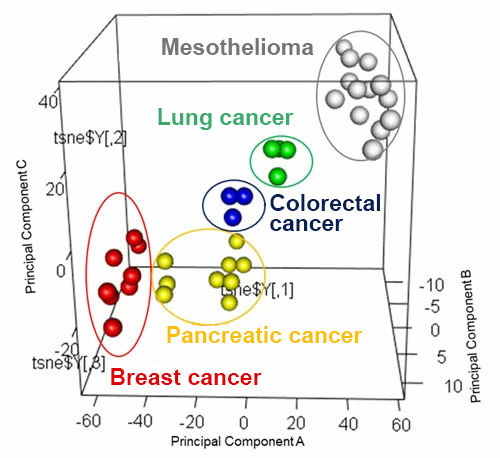

Through proteomics analysis of exosomes in blood, we can identify not only the presence of cancer, but also the type of cancer.

Axes values denote relative difference in composition, with points further away from the origin indicating greater difference.

A strong desire to help people can inspire research

Why did you choose a career in cancer research?

I love the periodic table, so I chose applied chemistry as my major at university. But while I was in college, a friend of mine was hospitalized with osteosarcoma. When I went to the hospital to see my friend, there were many children with pediatric cancer. I was shocked when I found out that many of the children pass away within three years. From that moment, I became determined to study cancer to help save children's lives.

After graduating from university, I continued on to the Graduate School of Frontier Science, Department of Integrated Bioscience at The University of Tokyo. In my first year of graduate school in 2006, I was shocked by what I learned at a guest lecture by Dr. David Lyden from Weill Cornell Medicine, who later became my mentor. The destination for metastasis of cancer cells was predetermined, and the location was already cultivated so that cancer cells could easily metastasize. Therefore, I felt that if we could understand what initiates this mechanism and develop treatment methods based on it, then that might save people's lives. I was filled with hope.

Why did you decide to study at Cornell University?

After the lecture, I went to ask Dr. Lyden, "What criteria do you consider for postdocs?" Then, he asked me, "When will you finish graduate school?" I answered, "In four years." I still clearly remember him smiling and saying, "That's a long way off!" That same day, I sent Dr. Lyden an email, and he replied. After that, we continued to exchange emails over the New Year's holidays. This led to me studying abroad in 2010.

Gaining a "be prepared" attitude

Is there a difference between American and Japanese research environments?

At American universities, things like race, gender, position, and research goals are all included and accepted as diversity. I have a 2-year-old daughter who was born in the United States, and the maternity leave there was very short. It was only 6 weeks in my case. Since children can't be taken to the lab, they set up a lactation room for me. People even shared various post-maternity advice, like how watching videos on your phone of your baby crying can help with pumping breastmilk. When I tell this to people in Japan, they are surprised, so I think Japan may also need a cultural shift so that going through life events like having a baby should be something that is easily accommodating.

Also, what was very helpful while I was at Cornell was my gaining a "be prepared" attitude. I learned to always be prepared so that I don't miss an opportunity. In the United States, there is something called "elevator talk" training. This is a career development training for honing your skills on how to highlight your abilities and seize opportunities in the tens of seconds you have when you are in an elevator with a researcher you admire. Elevator talk is also useful for presentations at academic conferences.

2010

2018

When Prof. Hoshino began working abroad, Dr. David Lyden's lab had less than 10 people. Only three of them, including Hoshino, were studying exosomes. Since then, more people have begun focusing on exosomes. Dr. Lyden's lab now has more than 30 members, all of whom are studying exosomes.

Is there a way of thinking that has helped you in your career as a researcher?

Ultimately, you can only do what you can do, so just do your best every day. The greatest fear of a researcher is that one day, another researcher will suddenly publish a paper on a topic that you've been working hard on. This is unavoidable because there are many researchers around the world working on the same topics. I think the only way to handle this is to try as hard as you can each day to convince yourself that you did your best and just couldn't make it in time. And the only way to do that is to devote yourself to your research each and every day.

In my case, rather than thinking "I want to be a researcher," I was motivated by the thought that "the only way to help these people is to become a researcher." The road to my final goal is still long, but I definitely hope to reach it.

But regardless, research is fun. Especially at moments when I realize that I am the only person in the world who knows about this phenomenon I am observing. This is something indescribable, and I truly feel happy to be a researcher. I hope that more young people will be able to experience this feeling.

I would like to build on my experiences in the United States to create a lab in Japan at Tokyo Tech where we can compete with the rest of the world.

Ayuko Hoshino

Associate Professor, Department of Life Science and Technology, School of Life Science and Technology

- March 2020-Associate Professor, School of Life Science and Technology, Tokyo Institute of Technology

- 2019-PRESTO Researcher

- 2019-2020IRCN Lecturer, Excellent Young Researcher, The University of Tokyo

- 2019-Adjunct Assistant Professor, Pediatrics, Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

- 2016-2019Instructor, Pediatrics, Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

- 2015-2018Scholar, Susan Komen Postdoctoral

- 2015-2016Research Associate, Pediatrics, Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

- 2013-2015Recipient of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Overseas Research Fellowship―Restart Research Abroad (RRA)

- 2011-2015Postdoctoral Associate, Pediatrics, Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

- 2010-2011Visiting graduate student, Pediatrics, Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

- 2009-2011Recipient of the JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (DC2)

- 2011Completed Master's Program, Department of Integrated Biosciences, Graduate School of Frontier Science, The University of Tokyo

- 2008Completed Department of Integrated Biosciences, Graduate School of Frontier Science, The University of Tokyo

- 2006Graduated Department of Applied Chemistry, Faculty of Science Division 1, Tokyo University of Science

. Any information published on this site will be valid in relation to Science Tokyo.